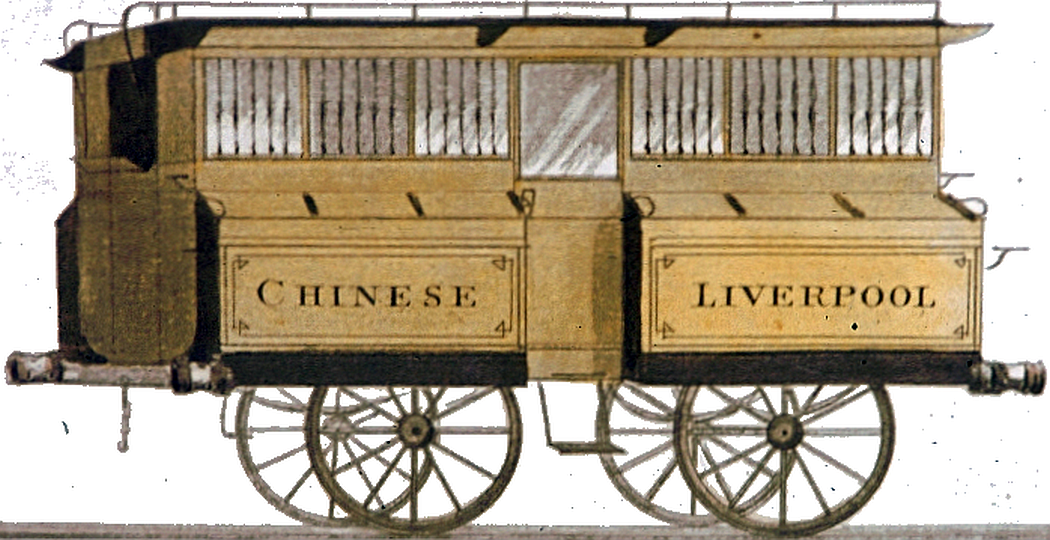

Some time ago I mused on the design of what I called the Chinese carriage, largely because the word "Chinese" was written on the side and it looked marginally pagoda-like end-on.

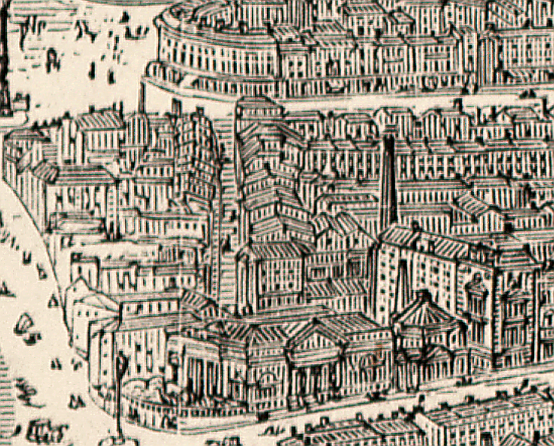

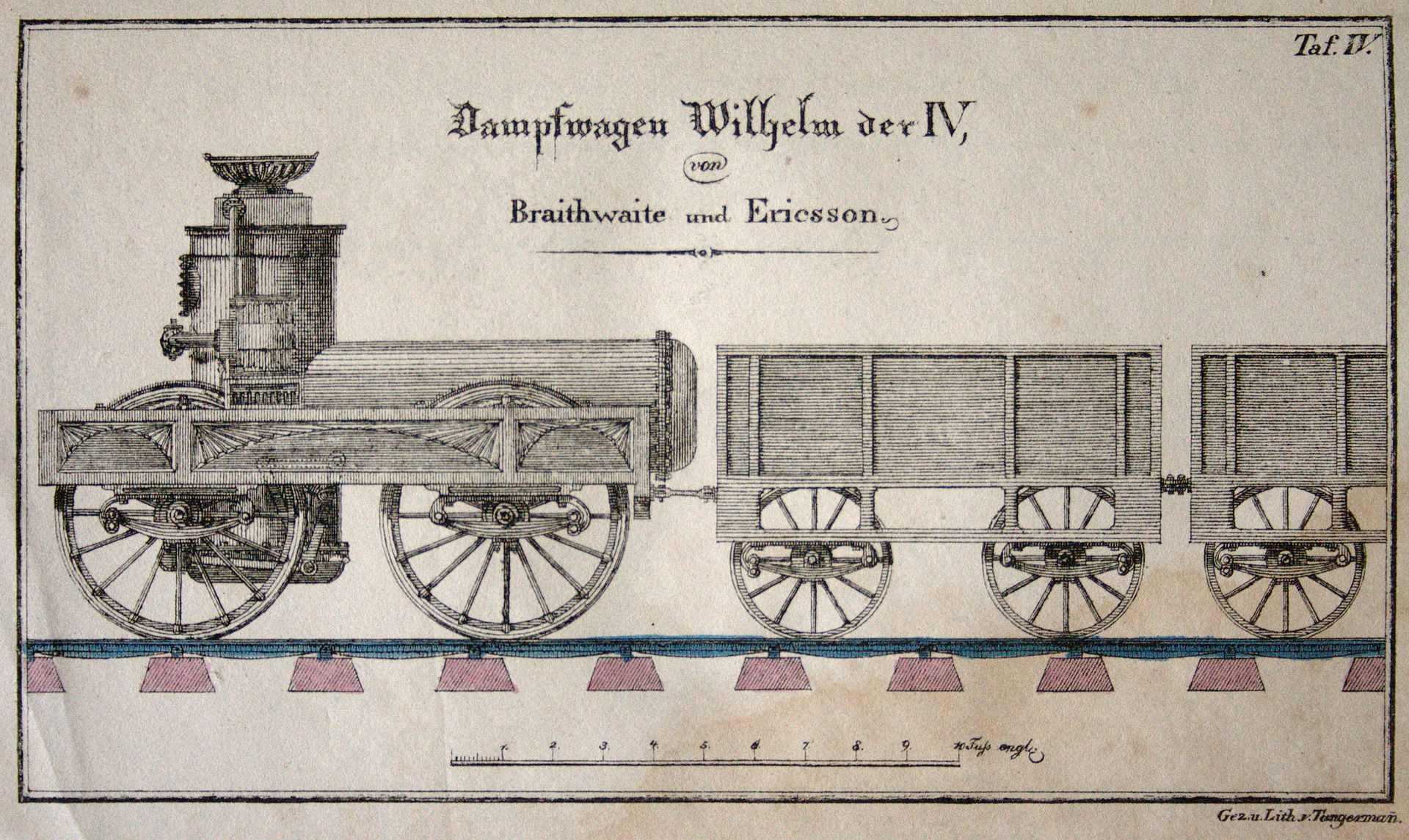

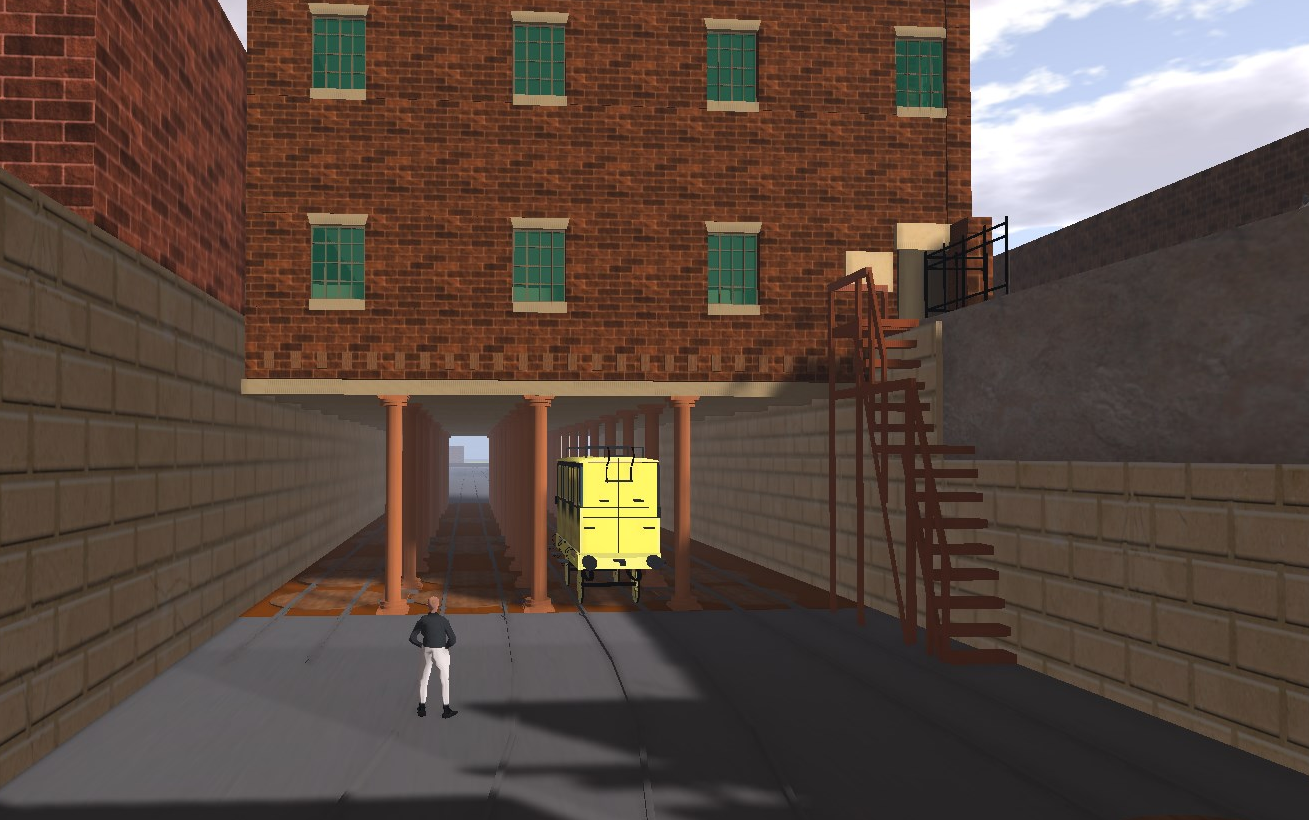

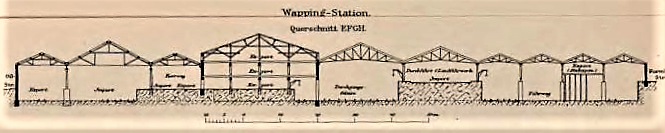

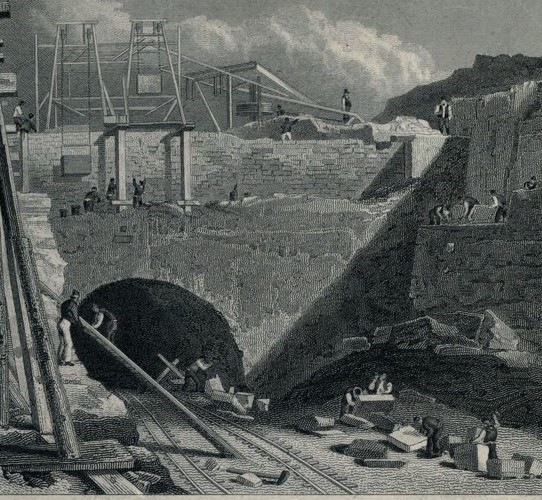

Thomas Talbot Bury's version

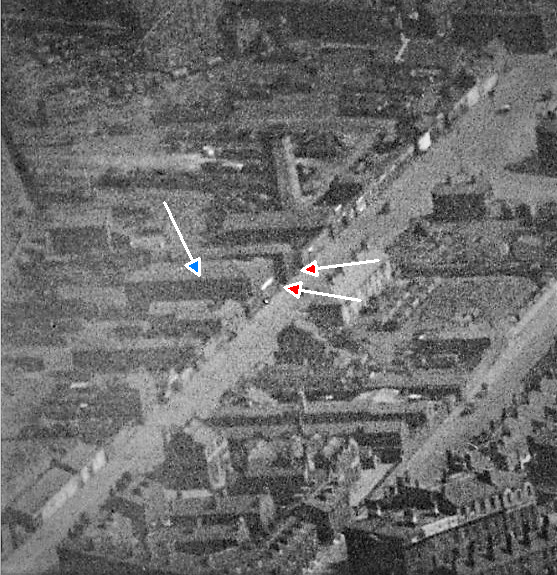

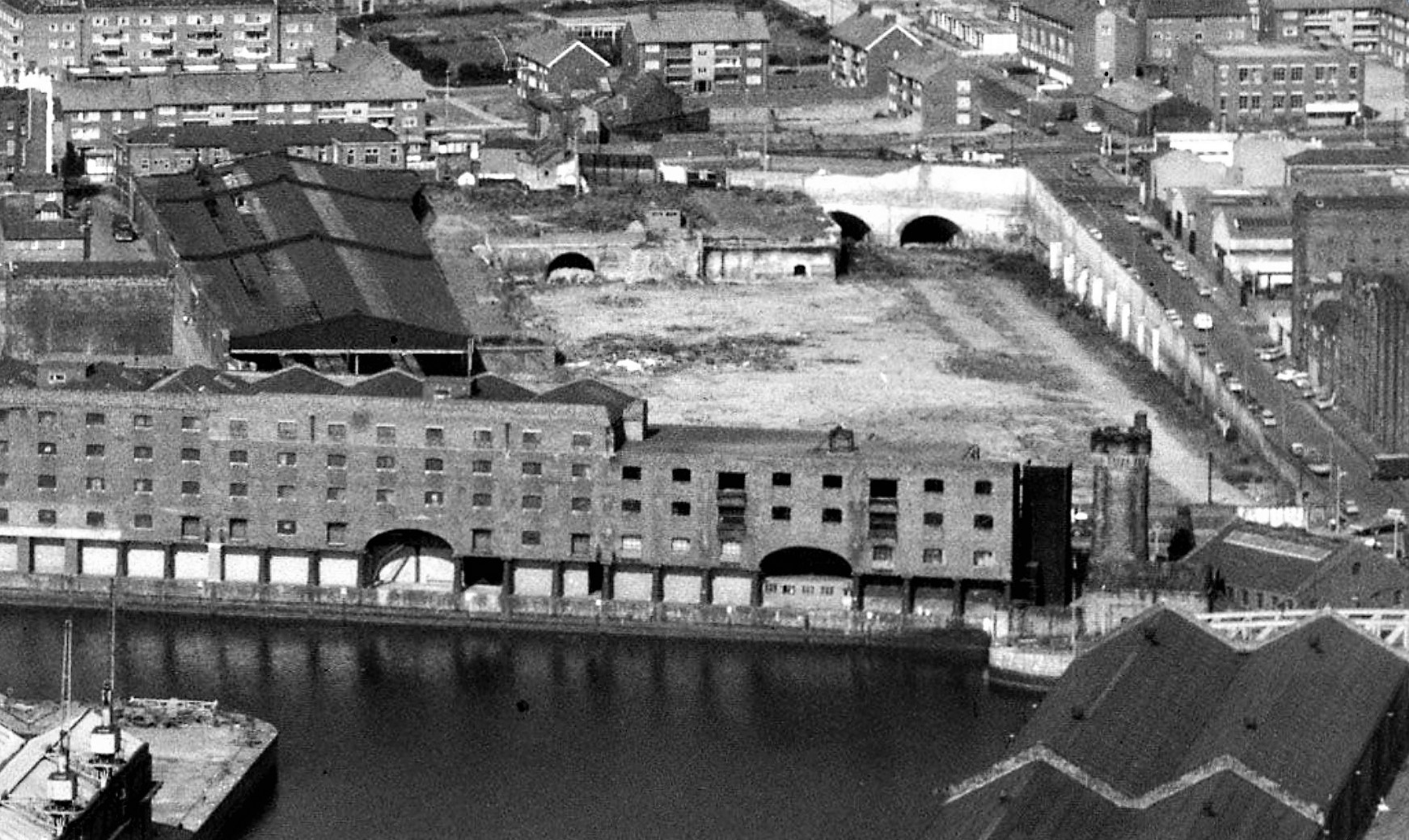

The carriage seen in Isaac Shaw's view of Crown Street, Liverpool

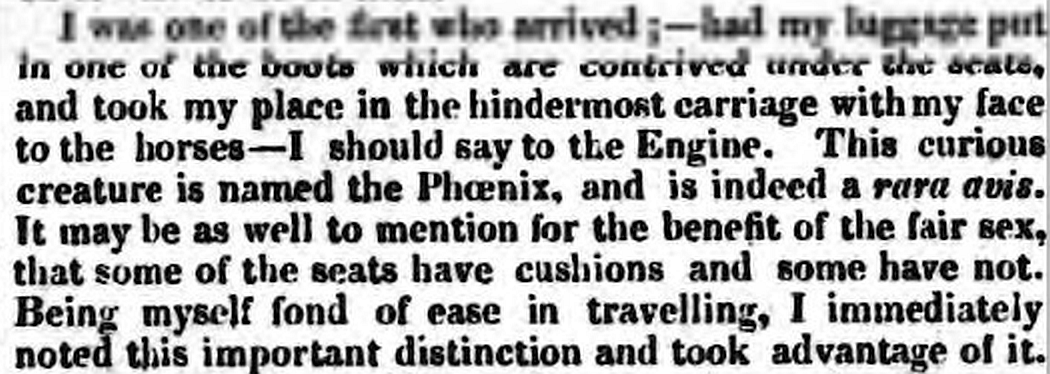

To be fair, I did consider the possibility that the side-bulges were luggage paniers (technically "boots" as per the holds fore and aft on stage-coaches) and so it appears they were, at least according to my reading of a letter published on October 2nd 1830 in the Sheffield Independent. The author was travelling from Liverpool to Manchester but appears to have found his own way to Crown Street station, chosen a comfortable seat facing the engine (presumably not in place at that time) and had his luggage stowed beneath a seat in one of the boots. So far, so unexceptional. Underseat storage was probably the norm.

(c) British Newspaper Archive

However, on arrival at Manchester, he waited for a porter to recover said luggage only to find that it had already been retrieved from the other side (which I take to mean "outside"). As he was sitting facing the engine, the boot was likely under another passenger's seat. So here we have a luggage compartment with two doors, one inside, the other outside.

(c) British Newspaper Archive

Whether external access is via the (rather narrow) lid or, perhaps more likely, the hinged vertical panel is unclear. In the former case retrieval is also awkward due to the height and the need to deal with what appear to be six boots either side of the carriage. Some haste will be in order if the train is due to make a return trip so it is perhaps unsurprising that the porters empty the boots as quickly as possible without entering the carriage via the proportionately smaller number of doors.

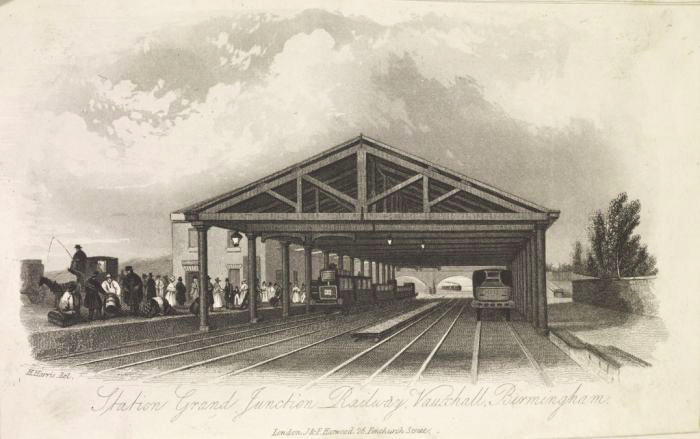

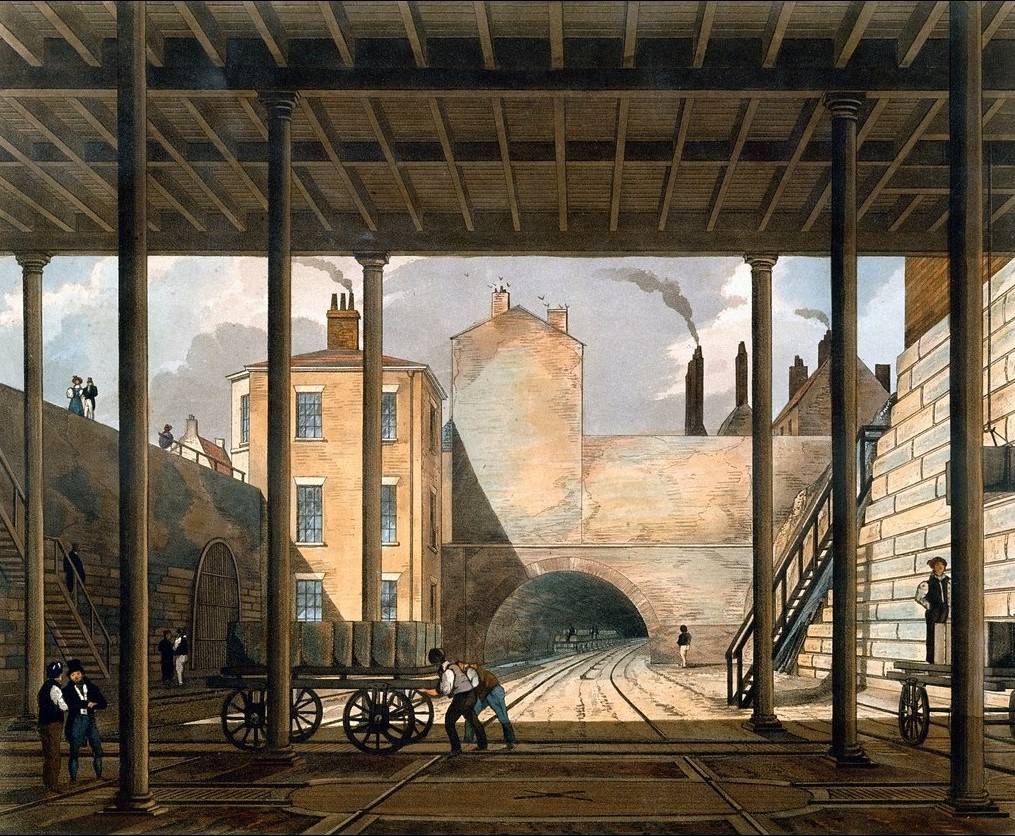

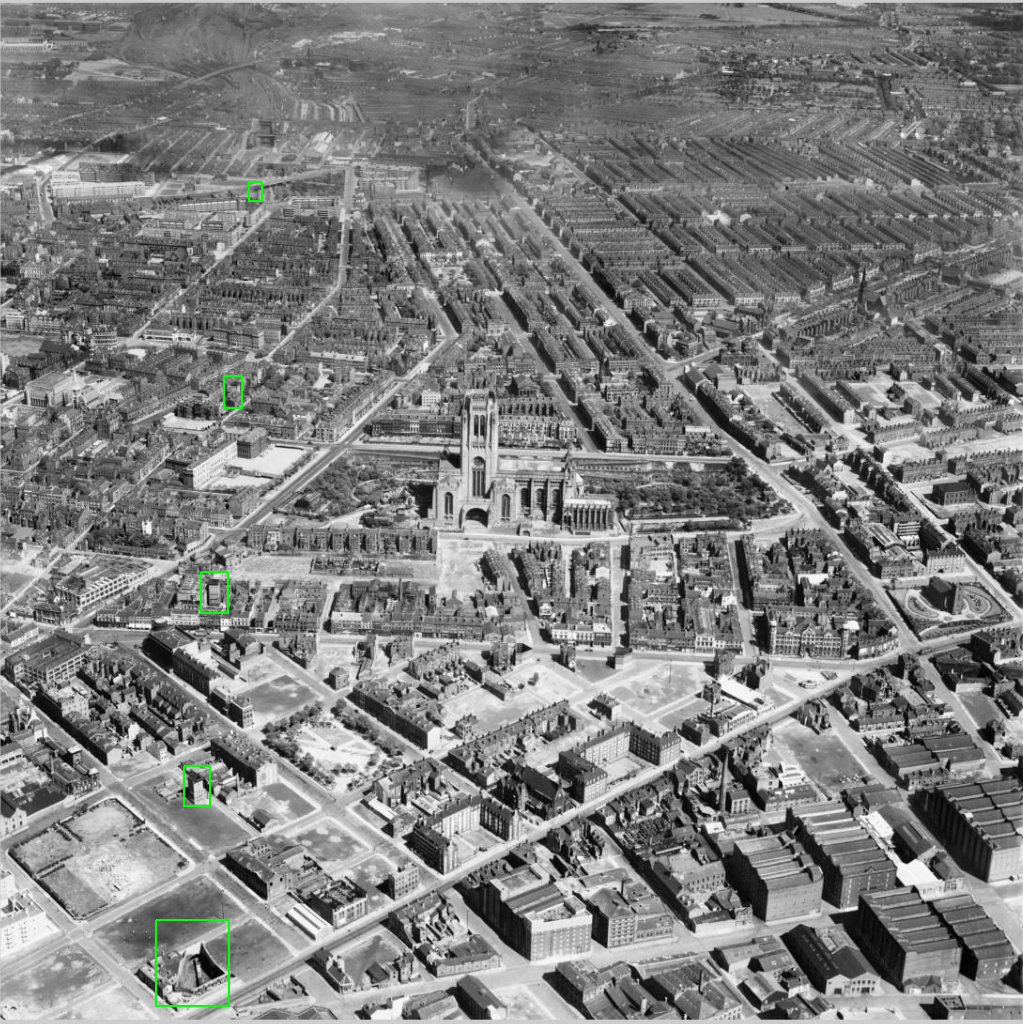

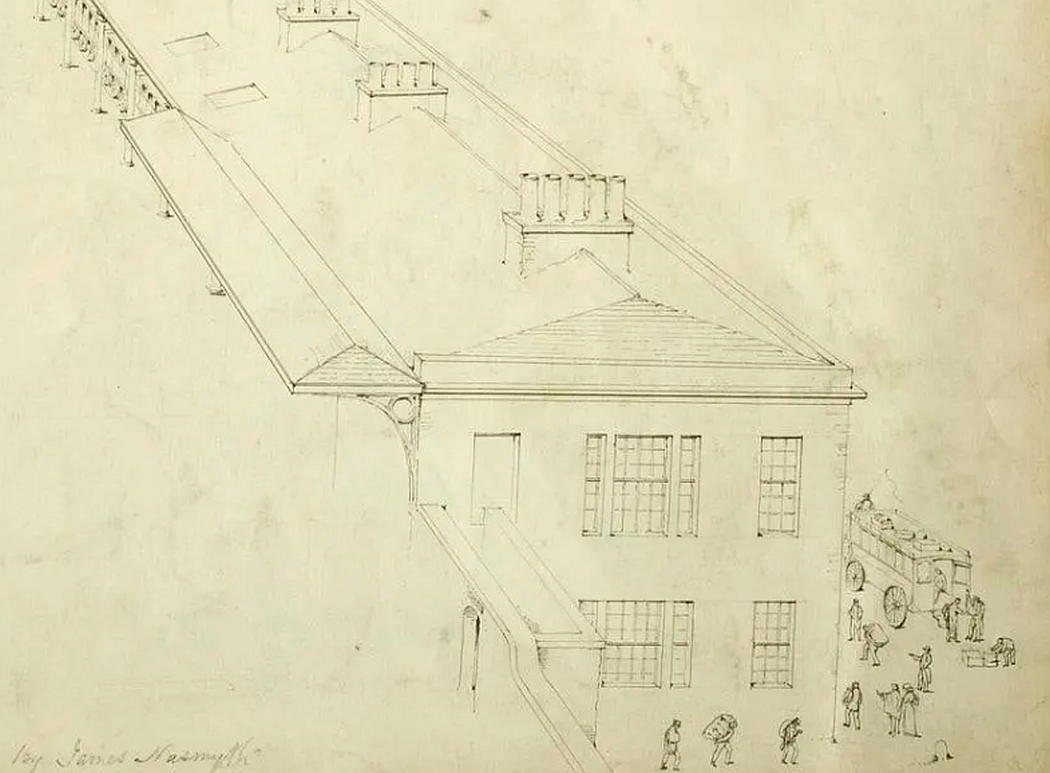

This is especially true for the arrival station at Manchester which was not opposite the departure platform (the 1830 warehouse was in the way) but on the far side of the Water Street bridge. James Nasmyth captured some of the fraught activity associated with an arrival with a host of porters carrying baggage down under the bridge and along to a horse-drawn omnibus parked outside the station entrance on Liverpool Road (Science Museum CC-BY-NC-SA).

The uncertainty was compounded by shared use of the boots without partitions and the presence of cads attempting to hijack passengers to rival hotels. Of course, there was also a facility to place luggage on the roof so the scene must have been one of organised chaos, especially to the uninitiated.

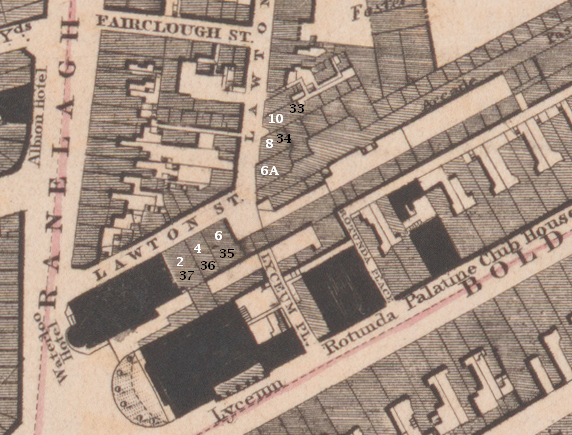

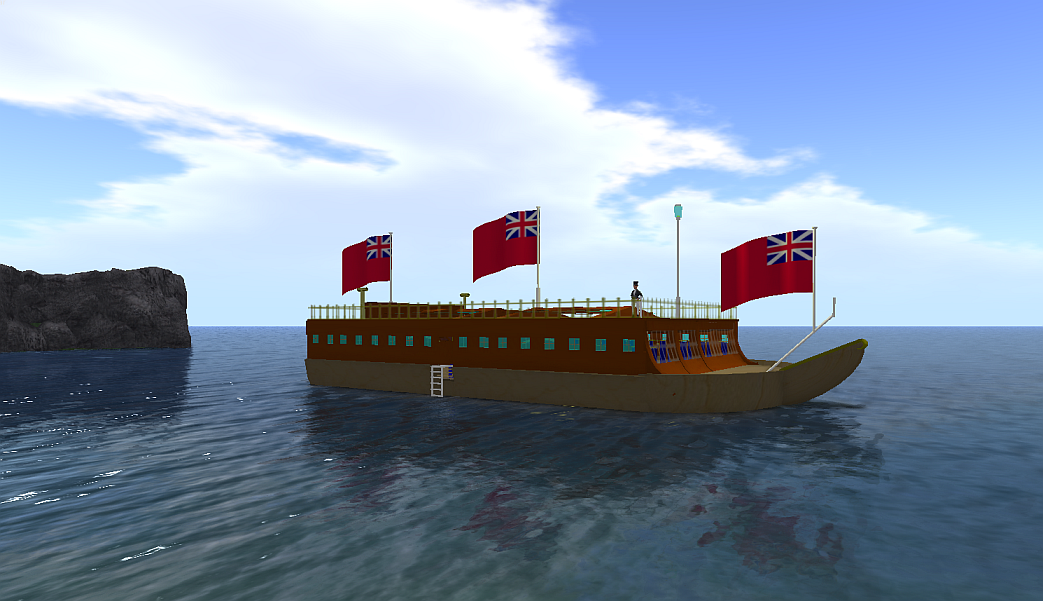

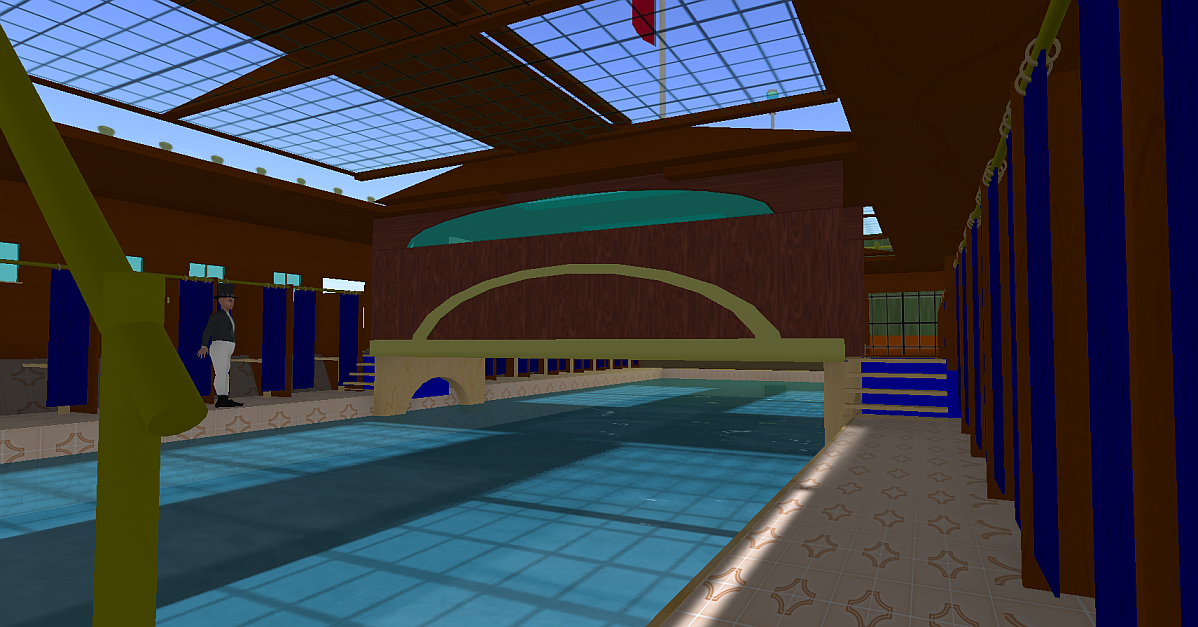

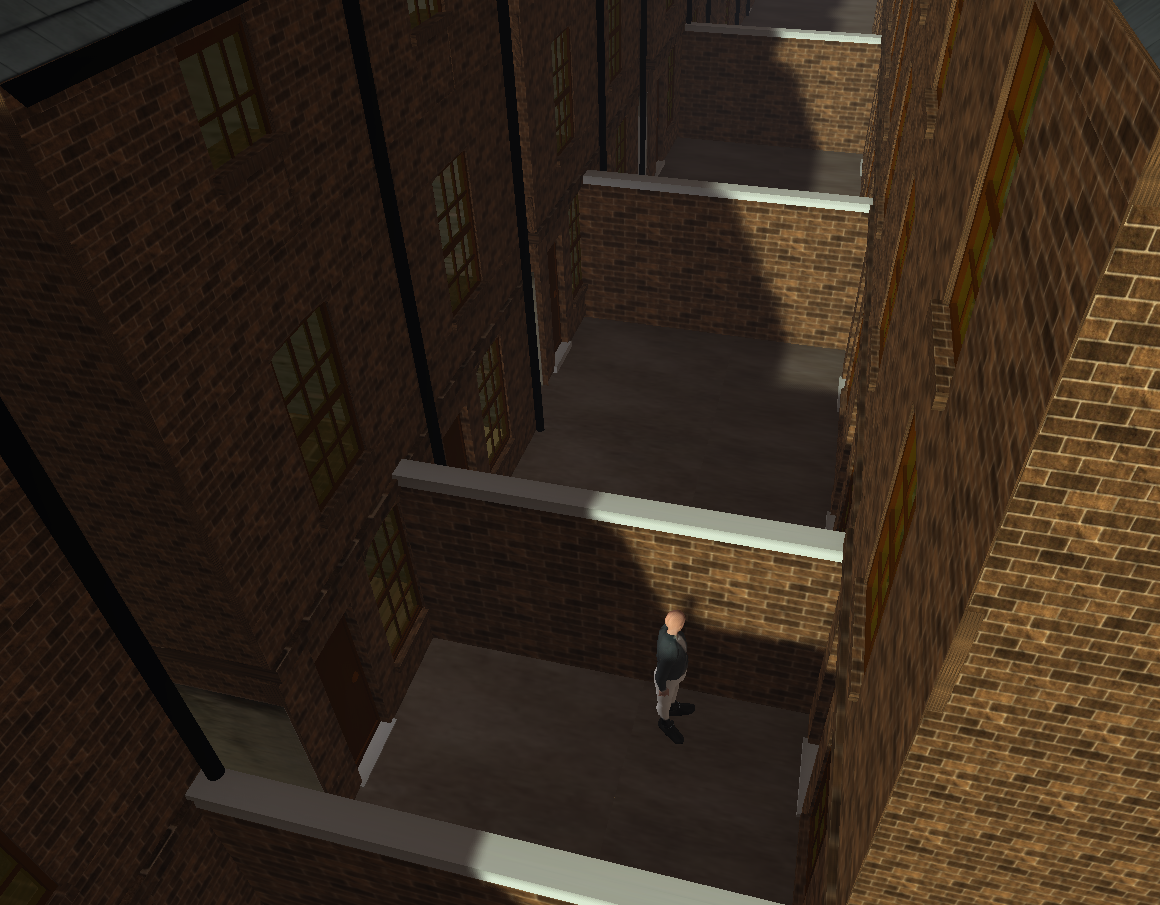

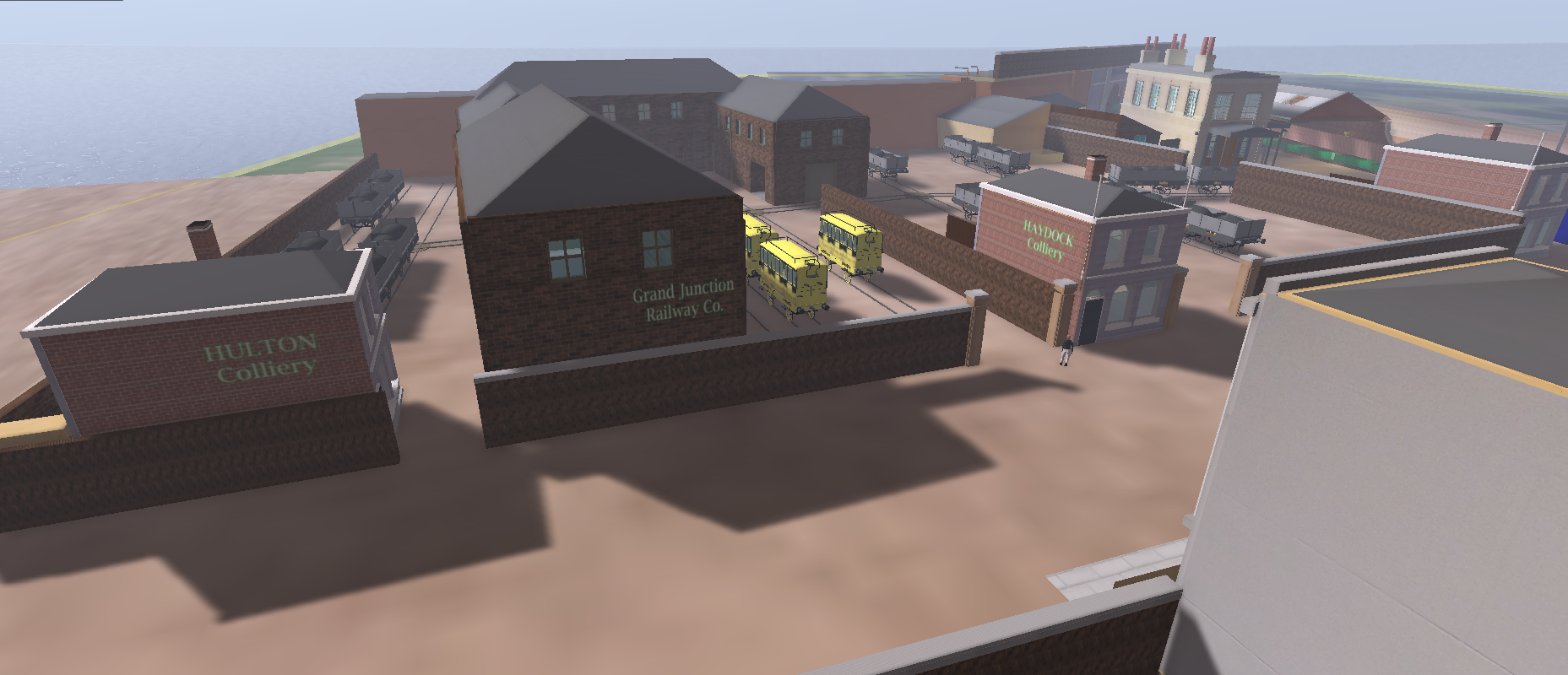

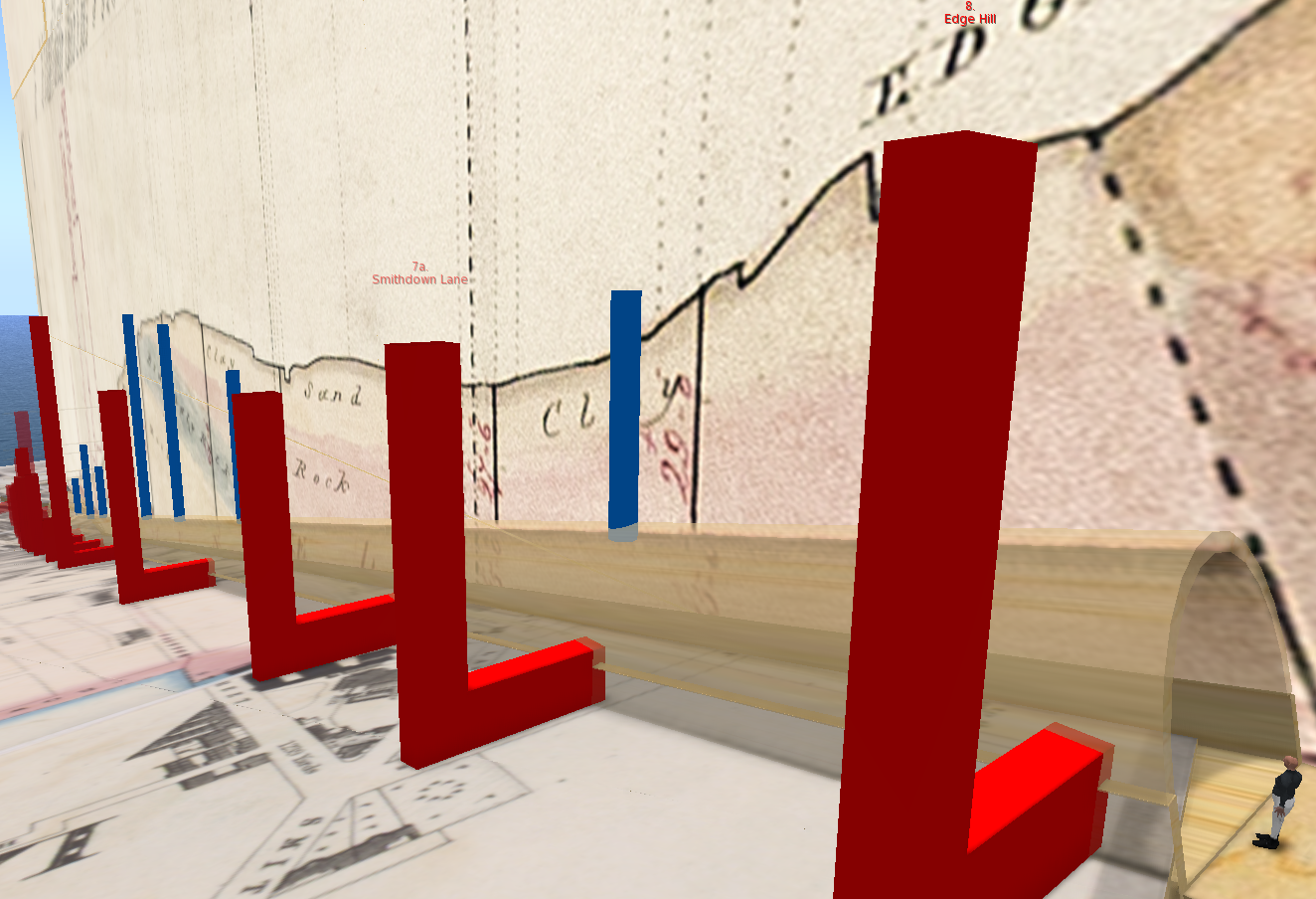

The OpenSim build

A quick build illustrates the possible layout of the Chinese carriage and, more importantly, some of the constraints. Firstly, the underseat storage is limited to seats along the sides of the carriage. The externals struts or edges to the boot lids suggest that these were shared in pairs in order to accommodate five seats per side per half-carriage yet still allow the end one a chance to open against the two (fully cushioned) seats against the end of the carriage.

This gives 24 seats per carriage which is the same as three compartments with four per side. It would be a tight fit, especially at the ends with the compensation perhaps of superior leg room compared to standard carriage designs.

Externally the drop-down side panel looks much the better bet although it might be argued that the roof overhang was, however briefly, to protect the boots when the lids were open. The handles visible in Bury's closeup at either end of the side panel might have been for lowering it as well as providing assistance on mounting.

Coach building

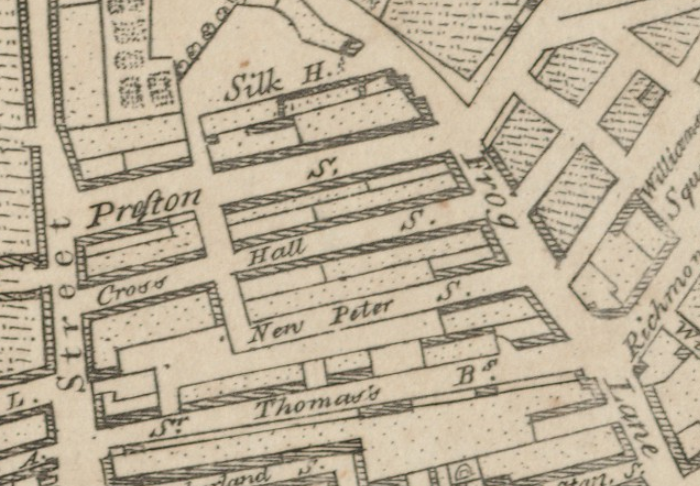

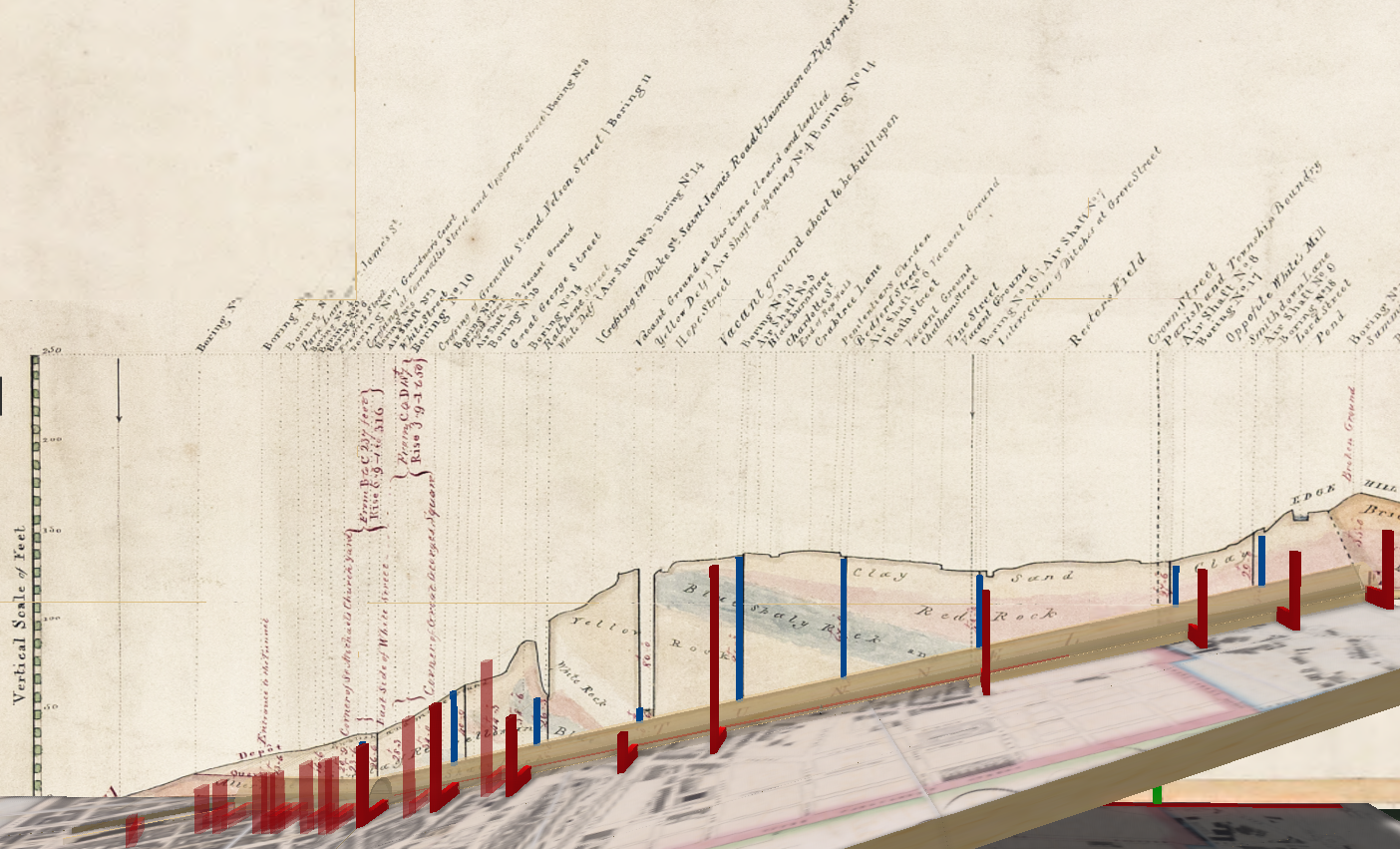

In 1828 Stephenson, acting on James Cropper's recommendation, hired coachmaker Thomas Clarke Worsdell to manage construction of the carriages and pertinent items start to appear in the Finance Committee minutes from 23rd May onwards, e.g. red pine timber, mahogany, beech, wheels, axles, iron plates, brass coach furniture, broad cloth and fringe for coach lining. In January 1829 files were ordered for the coachmakers and in February paint. The choice of yellow was made by Stephenson based on the colours used by the fastest road carriages.

The designs were heavily influenced by road coach designs, for example the multi-compartment diligence. Initially many different designs were adopted and these are described in an article published in the Liverpool Mercury on 11th June 1830. The Chinese coach design is not mentioned; indeed, there is specific mention of the lack of space for luggage.

(c) British Newspaper Archive

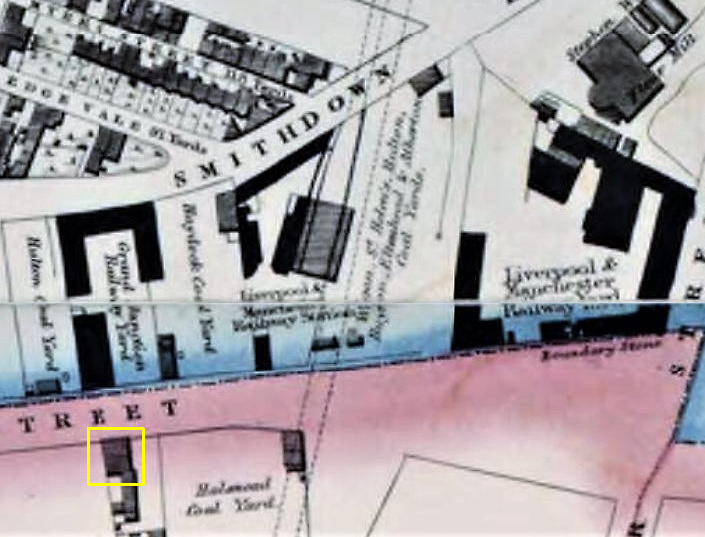

Construction and maintenance took place at Crown Street but transferred to Lime Street when workshops were completed at the new station which opened in 1836.

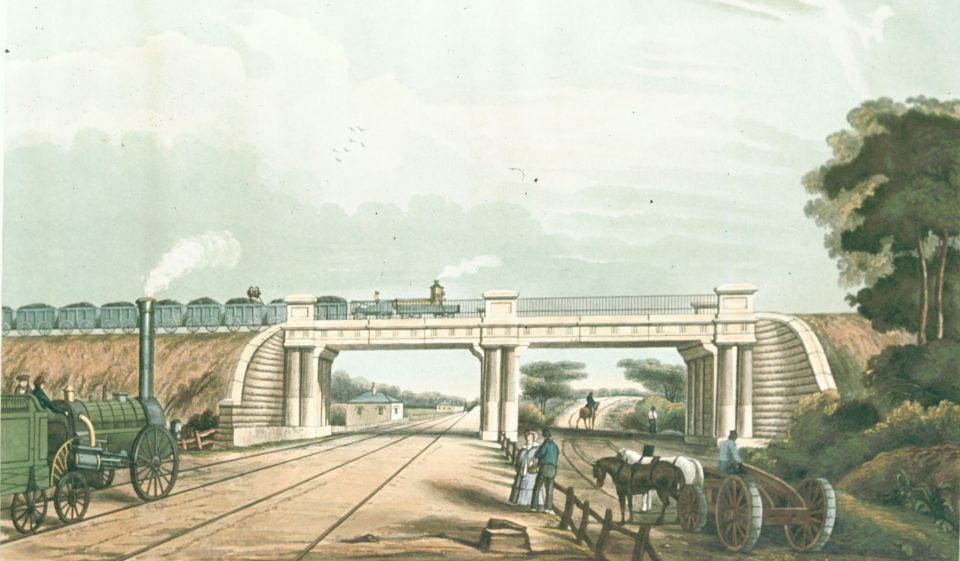

An inspection run on 14th June 1830 may have seen the first public use of Worsdell's carriages. It employed the locomotive Arrow, two coaches, an open carriage (presumably blue, second class) and seven waggons. It started in Liverpool and went as far as the Oldfield Road bridge, the bridges into the Liverpool Road station still being under construction.

Coach names

Most prints show the carriage name on the centre door. This does not seem to apply to the Chinese carriage which appears in three early prints, two by Bury and one by Shaw, raising the possibility that there was more than one carriage of this design, named or otherwise.

Names from Thomas, p. 253.

Velocipede, Lord Derby, London, Fly, King William, Queen Adelaide, Duke of Wellington, Sir Robert Peel, Earl of Wilton, William Huskisson, Marquis of Stafford, Sovereign, Clarence, The Lark, Greyhound, Traveller, Harlequin, Victory, The Delight, The Times, The Globe, Experience, Treasurer, Despatch, Conservative, Reformer.

Possible names from 1828 minutes of the Finance Committee

These derive from invoices for wheels, axles, etc mentioned in passing.

Cumberland, Nimble, Jean, Jenet, Hope, Bellona, Mercury, Eleanor, Expedition, Anne, Betsey, Jane, Turtle Dove.

Given the absence of overlap, it is possible that these names were used during construction and changed subsequently. Otherwise it suggests that there may have been about 40 glass coaches not including any subsequently built for the mail and, perhaps, the Chinese carriage(s).

Beyond the L&MR

Names do not seem to have persisted beyond the mergers of the mid-1840s. It may be that the railways by that stage were keen to distance themselves from their road forebears rather than mimic them.

Likewise, the L&MR does not seem to have adopted the saloon or external boot layouts to any great degree. Perhaps negative feedback from passengers, the availability of the roof and the requirement for access from trackside were sufficient disincentives.