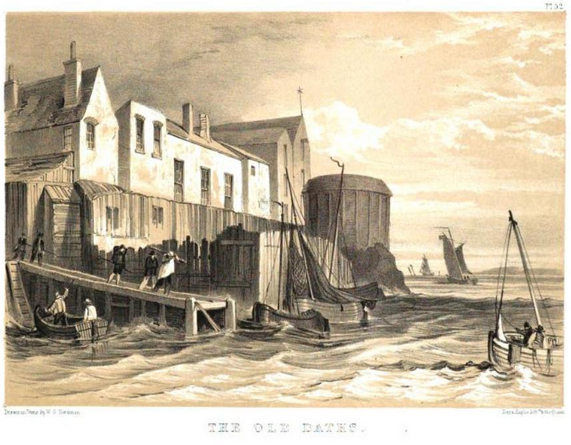

Tourist guides to Liverpool were extolling the virtues of bathing in the Mersey estuary as early as 1803. There were seaside hotels up at Bootle and bathing machines and private baths established nearer the growing town around 1765. In 1794 the corporation acquired the latter which had separate facilities for males and females with 30 x 33 ft baths and the option of sea swimming when the state of the tide allowed. However, as the docks extended northwards so the baths became separated from the estuary and they ultimately closed in 1817.

Fig: The old baths off Bath Street.

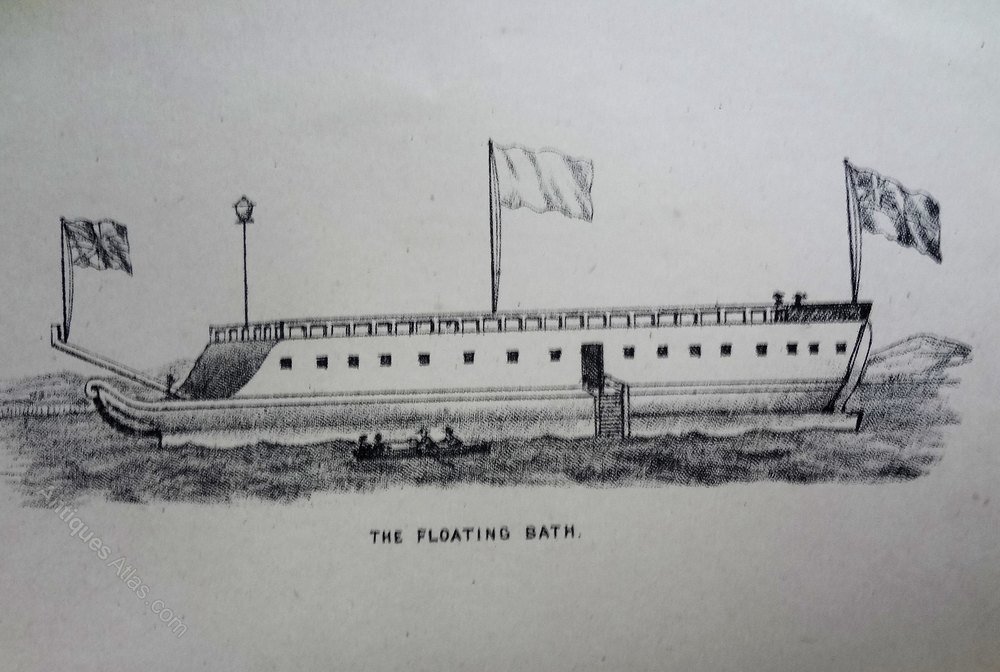

While the corporation pondered its next steps, private enterprise stepped forward in 1816 in the guise of Unitarian Liberal Thomas Coglan. Coglan's approach was radically different in establishing a floating bath in a ship moored some distance offshore. Floating baths were nothing new; continental examples dated back to the 1760s and London had one on the Thames established by a Mr Fox in 1810. However, mostly these were moored at the riverside unlike Coglan's which was variously 200-400 yards from the docks.

Fig: Mr Coglan's Floating Bath

The reason for this seems to have been the common practice for males to bathe naked and the perceived need to remove such outrageous behaviour from public view. Although most sessions were male-only, the Liverpool floating bath later instituted 1-2 female-only sessions per week (females sometimes also bathed nude as became apparent in 1880 when the floating bath at Bridgnorth sank during one such session, leaving the doubtless distressed participants to swim to the bank minus their clothes).

Who was Thomas Coglan?

Coglan (??-29/06/1841) was a Dublin-born auctioneer and stocks and shares broker. Family records suggest that by 1818 he was living with his wife Martha on Denison Street. This was close to the north shore and it is possible that Coglan was an enthusiastic swimmer as well as having sufficient means to fund a venture potentially at odds with the corporation's own plans.

He was an early trader in railway shares, a founder member of the Liverpool Stock Exchange and stood successfully in the St Anne's ward as a Reformer for election to the council in 1835 and 1838. On his demise his wife Martha held a substantial investment in the Bank of Liverpool.

As the docks expanded northwards Coglan moved to more affluent Bold Street where he appears to have lived over a business offering warm and vapour baths, perhaps run by Martha given his other interests. According to Horwood's 1803 map, 19 Bold Street was likely on the east side between Newington and Heathfield Street, perhaps the extant three-storey terraced building with quoins and eared architraves around the windows.

Fig: Possible 19 Bold Street according to old street numbering scheme (ex Google Maps)

In the 1830s Coglan moved to Stafford Street, now in the so-called Fabric District.

Coglan's commercial offices were initially at 3, Statham's Buildings, 84 Lord St, although he later moved to 19/21 Exchange Street East. Statham's Buildings were probably affected by the widening of Lord Street in 1828/9 following the Act of 1825.

Construction, launch and early operation

Coglan's Floating Bath was constructed in Hamer's yard and launched on 11th June 1816 to great acclaim, providing a welcome diversion from the election then underway. The £3000 expense of fitting-out a purpose-built ship was supported by a scheme that guaranteed four years of free swimming for £20. Many doubtless also saw it as a public "good" in terms of encouraging healthy exercise and a useful skill while at the same time mitigating the problems off the north shore.

While tourist guides advanced the tonic properties of immersion in cold water, Liverpool doctor James Currie was one of several who identified possible medicinal properties, including in his case treatment for typhus. Nevertheless, the floating bath was a summer-only operation, retiring to the then undeveloped Wallasey pool over the winter.

The ship had buoyancy tanks that allowed it to carry estuarine water that entered and departed via grated sluices at either end. According to Samuel Holme it was initially moored some 400 yards off Pier Head, i.e. Georges Dock, which would place it not far off midstream, handily avoiding whatever effluent emanated from the town and docks. This exposed location may go some way to explaining its sturdy ship-like design. By 1838 the ship was moored 200 yards off Prince's Dock where the middle of the three flights of steps was used by prospective clients.

The facility was open from 06:00 to dusk for a fee of 6d for children and 8d for adults with season tickets also available. The ship appears to have had a rudder or tiller, suggesting that it may have reoriented during the course of the day to face the oncoming tide.

According to one source, the vessel was 82x34 ft with the bath 80x27 ft (and hence larger than the new corporation baths on George's Dock that opened in 1828) with a floor sloping from 3.5 to 6 ft in depth of water. There were numerous dressing-rooms around the pool and some were screened to permit bathers to descend into the water unseen. There was also a small private bath and additionally two cabin areas aft and midships where food, drink and newspapers were available. Strong swimmers could also emerge from the far side of the ship and swim in the estuary itself.

After their swim bathers could go on deck and either promenade or use the tables and seating provided.

Social function

In his autobiography Holme pays tribute to the floating bath for improving his swimming skills and as a young man reckoned on spending an hour there at high tide 2-3 times a week during the summer months. He recalls taking "headers", ie diving, into the water, either from a board 7 ft above the waterline (presumably at the doorway or on the foredeck) or from the promenade deck some 15 feet above.

Clearly the bath was also a place to mix socially and Holme notes that Egerton Smith, founder/publisher of the Liverpool Mercury, was one of the best swimmers. It is perhaps unsurprising then that another of Smith's publications, The Kaeidoscope, published an anonymous letter from son to father begging for a season ticket as well as a piece by Coglan on the benefits of vapour baths.

While Holme went onto a successful career as a builder (St George's Hall was one of his) and Tory Mayor of Liverpool, more radical elements also met at the bath. Thus on a visit London publisher Richard Carlile used the excuse of a swim to encounter Egerton Smith and his Mercury colleague John Smith who, like Carlile, had been at Peterloo in 1819. The Smiths may have used the informal atmosphere of the floating bath as a general means of gauging public interest and sentiment.

On at least one occasion the ship was used as the base for swimming races in the river albeit with limited success as the strength of the current forced many to retire. Nevertheless, it attracted thousands of spectators on the dockside.

The new baths

Fig: The new baths designed by corporation architect John Foster Jnr.

In 1828/9 the corporation finally built new bathing facilities on the west side of George's Dock and concern was expressed that this would damage Coglan's trade and investment. However, it is clear from his dealings in a number of railway shares that he remained solvent and his death in 1841 preceded the crash in railway shares in the middle of that decade.

Tourist guides show that the bath continued to operate until at least 1843 although it increasingly became an impediment to shipping.

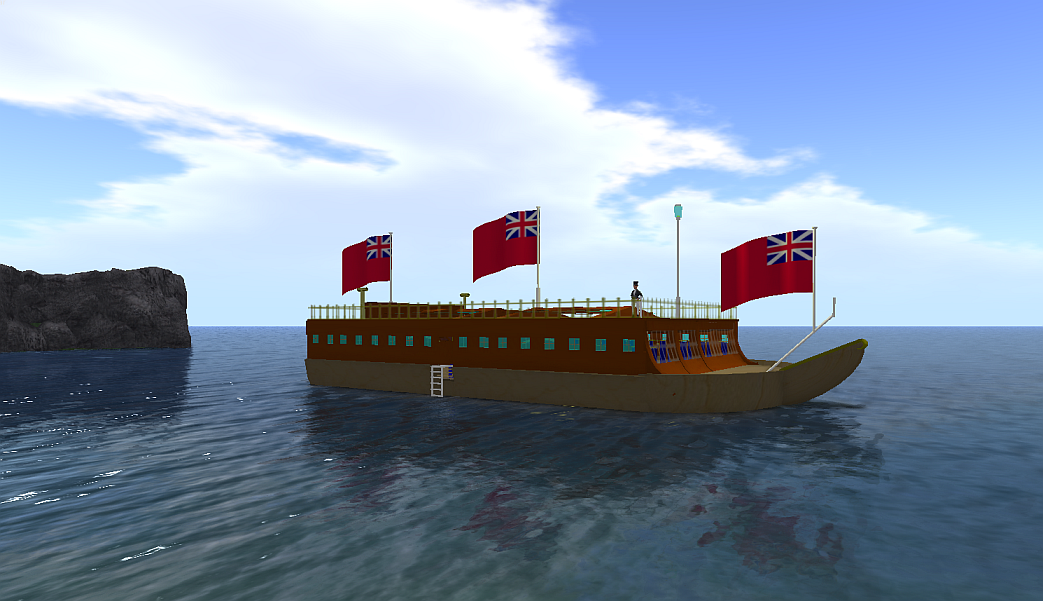

The OpenSim model

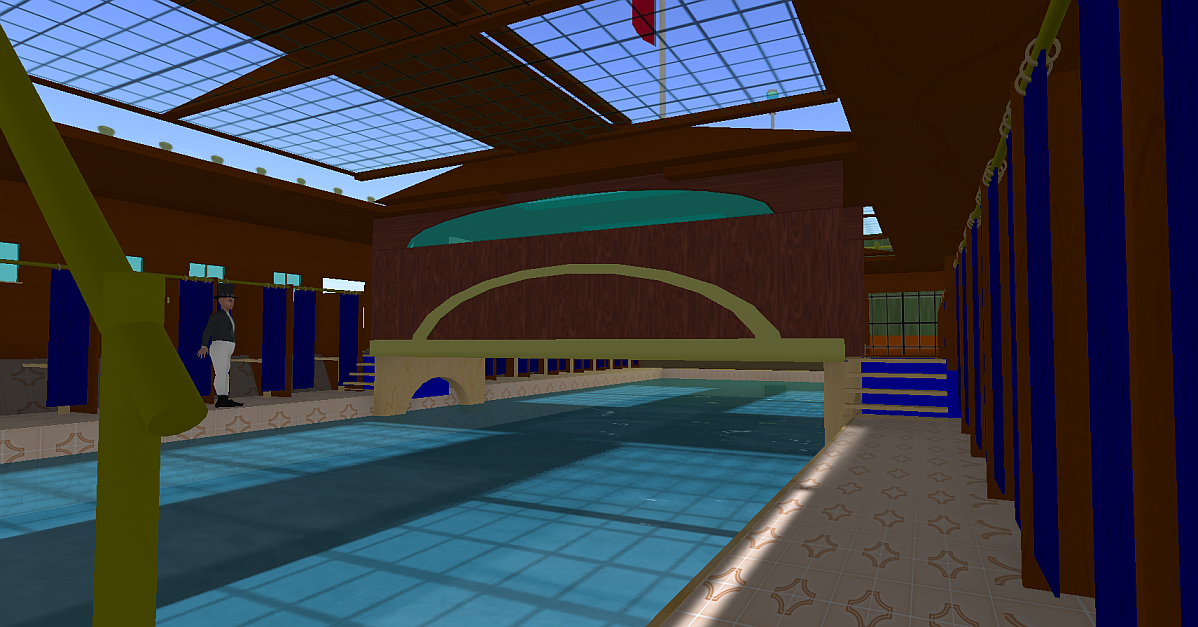

A tentative OpenSim model has been constructed. There is apparently a Herdman illustration of the interior but this could not be found online so a design has been adopted based on the above description.

Fig: Exterior view

The standard representation of the ship shows a hull with a row of portholes and a door roughly midships. The deck above has railings but little obvious superstructure beyond a flagpole. It seems likely therefore that the door gave access to the central cabin which presumably bridged the actual pool as well as providing access to the poolside.

The portholes presumably open above the changing cubicles and thus provide light to both cubicle and pool. Given that operation ceased at dusk, it seems not unlikely that the deck incorporated one or more skylights.

Fig: Interior view

The published measurements allow for a poolside margin but no space for cubicles. Accordingly a metre is added at either side for changing space. It is assumed that these were dedicated to individual customers so no separate storage area for baskets is assigned. If that was the case, it caps the number of swimmers at around 32 although there are reports of as many as 500 using the baths in a day.

The aft area also had a cabin space and it is possible that the small private bath was also located here. his area has some superstructure. While this may in part be related to the tiller, it is also possible that a kitchen was located here and two small chimneys protrude on the superstructure. It may also have housed the staircase to the promenade deck.

Nothing is known of the staffing arrangements on the ship although with at least two rowing boats and presumably some management and galley provision, it seems likely that 4-6 people were temporarily employed. There is no evidence of swimming tuition or supervision though the pool boasted not a single casualty in the 27 years of its operation.

See also a more general review of Liverpool as a coastal resort.