Liverpool Crown Street station was the western terminus of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway (L&MR) which opened in 1830, arguably the first modern railway. While looking for parch marks at Crown Street recently, an intriguing depression was noted that raised the possibility that this was the site of the shaft or eye used to construct this section of the Wapping Tunnel. This famous tunnel took wagons down to the Park Lane goods station close to the Mersey docks. The start of the tunnel was in the Cavendish cutting east of Crown Street where the stationary engine in the Moorish Arch was used to pull the wagons back up.

Fig: Crown Street park looking towards the entrance on Crown Street and the adjacent ventilation tower which stands above a shaft down to the Wapping tunnel. The depression is highlighted and a curved parch mark can be seen between the depression and the tower.

The tunnel

There were some eight shafts (or eyes) used to construct the Wapping tunnel and conventional wisdom suggests that the LNWR reused five of these when they built the ventilation towers in the late 1890s so that locomotives could work the tunnel. The ventilation tower at Crown Street was built in 1899 and is one of the few visible reminders of Crown Street's connection with the early railway. On the opening day on 15th September 1830, the trains started at Crown Street but on their return went down the Wapping tunnel.

The tunnel was built by contractors working in either direction from each eye, normally some 200-300 m distant. The call for tenders went out on 23 August 1826 and closed just over a week later on 2nd September. However, purchase of the field at Crown Street was not agreed by the Board until 15 Jan 1827 so there may have been some delay in starting there unless special arrangements were made with the owner of the field and nearby mill, Stephen White. .

Work had, however, started some time before 19th Feb 1827 as at the Board meeting that day the Principal Engineer George Stephenson recommended that the price of most contracts be increased due to the poor quality of the stone extracted (contractors were allowed to sell the stone they quarried and the return was presumably lower than anticipated). Stephenson listed six shafts particularly affected rather than the eight in the tender document:

White Street

White Delf

Yellow Delf

Mosslake Fields (Copelands [the contractor])

Millers Close

Penitentiary Drift

They appear, however, to be in the same numerical order with the former White Street shaft being closest to Park Lane/Wapping. Millers Close presumably refers to the parcel purchased from White.

Penitentiary Drift may refer to an additional shaft required to correct for an error of 13 feet made in surveying by Vignoles or, more specifically, to the person he delegated to do the poling while busy elsewhere. In 1824 the Liverpool Female Penitentiary was located at the corner of Mulberry Street (which extended much further than now) and Crabtree Lane/Falkner Street (27 on map) which is on the general line of the tunnel and presumably close to the site of the supplementary shaft. The source of the error was discussed at some length in a letter from Vignoles to his sponsor Riddle. Stephenson made a considerable fuss and, disregarded, Vignoles reluctantly resigned on 2nd February 1827 although he subsequently went on to a distinguished career in civil engineering.

The eye at Crown Street

The tender document specifies that the shaft should be "at the centre of the lot they contract for" and, although unstated, close to the line of the tunnel. Even allowing for a less well defined boundary, the Crown Street ventilation tower is decidedly off-centre while the candidate eye is in the expected location. Of course, the definition of a specific "lot" might have a bearing, in this case it simply being "field E(ast) of Crown Street".

If Gage's 1836 map is accurate, then the Wapping tunnel runs roughly parallel to the station with its western edge coinciding with the wall dividing the passenger station from the adjacent Millfield station as seen in Bury's print. If we assume that the northern face of the eye was 30 feet from this dividing wall and the tunnel below, it would place the eye close to the station platform/verandah.

Two consequences arise. Firstly, the eye may have been contiguous with a basement level in the station building. Perhaps more significantly, it makes it less likely that the station was built at the same time as the tunnel excavation was taking place or, indeed, at the same time as the workshops, stores and stables. The latter were completed by July 1827 when payment of the roofer was agreed by the Finance Committee. This may in turn make it less likely that Stephenson and Gooch designed the station as part of the first tranche of buildings (there is no specific mention of it) although the general position of the station was necessarily determined at an early stage.

The LNWR plans for the Crown Street ventilation shaft and tower make no obvious mention of a preexisting shaft but do provide interesting data. The depth of the shaft above the tunnel is of the order of 18 feet which, when added to the height of the tunnel (16 feet), gives a total of 34 feet compared to the 30 feet mentioned in the tender document. This difference may be accounted for in part by the distance between the two and the gradient of the tunnel (1 in 48); there may also have been some exploratory work in advance of the tender. In any event it does suggest that the ground had been levelled by this stage instead of sloping up to Smithdown Lane and adding to the depth of shaft required. The tender document refers to the use of wagons and rails to move the stone, clay and spoil away from the eye which also suggests that the ground would need to be reasonably level.

The eye itself was only 6 feet x 10 feet in cross-section. The depression in the ground at Crown Street has an oval shape elongated towards the tunnel suggesting that the passage to the tunnel, some 20 feet away, was only 6 feet wide although Engineering Timelines suggests a passage nearer 8 feet square. Even so, it is possible that there might have been "rooms" off this passage way, most notably stables for the ponies responsible for hauling wagons on the temporary narrow gauge railroad extending into the tunnel. According to Thomas (1980), these animals only emerged into daylight once passage to the surface via the tunnel was possible. Proximity to the air intake might have made their situation marginally easier to bear.

Although stone and clay had some value, general spoil was carted either for immediate use to fill holes or make embankments or for temporary storage prior to such use. R Gladstone in the Board minutes of 8 Oct 1827 suggested that stone etc from the Millfield shaft be transported by a temporary railroad in front of the Botanic Garden to the low ground between the front of the Botanic Garden and Abercromby Square.

Telford's cross-section (Update 23/04/2019)

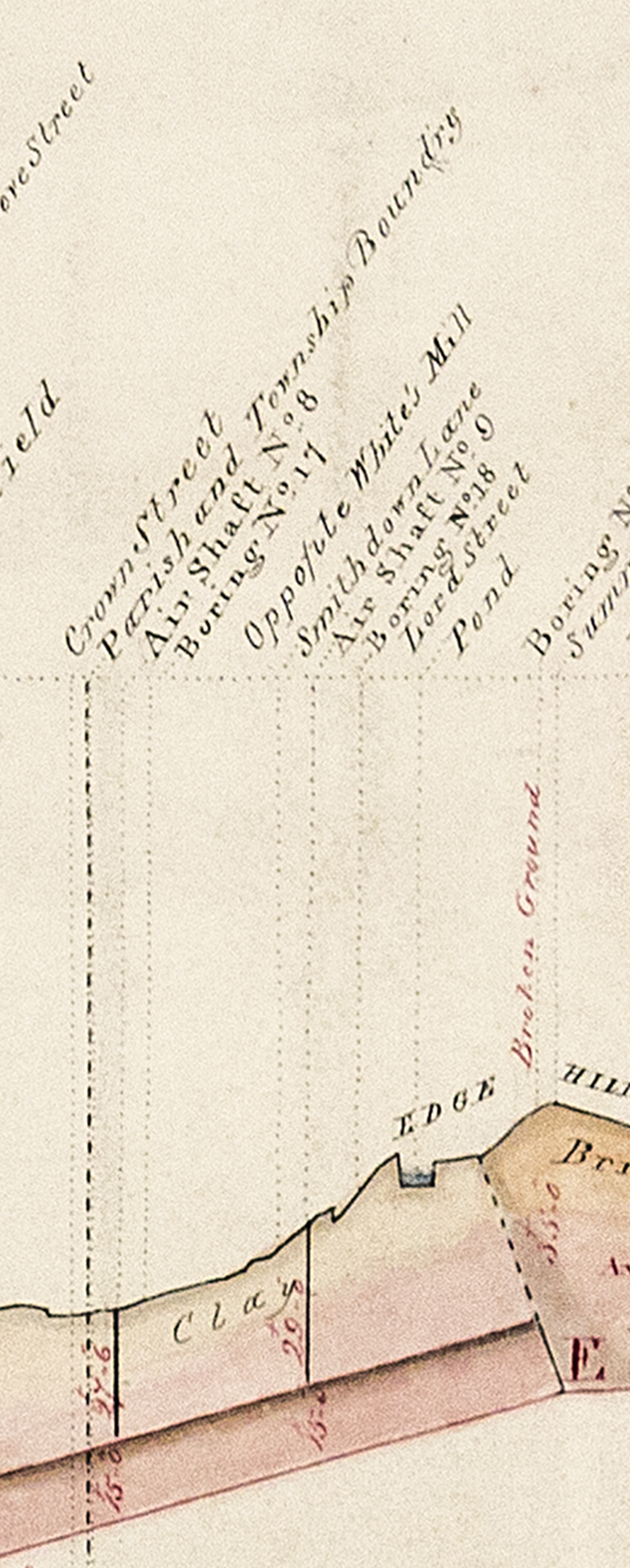

Paul from the L&MR Trust recently posted a cross-section from Telford's survey of the tunnel as it passed under Liverpool. Although subject to interpretation, it appears to suggest that there were TWO shafts at Crown Street, an air shaft roughly in the position of the existing vent and which may have been reused in its construction and a shaft termed "boring #17" which presumably represents the location of the eye. The latter appears to be roughly 48 m east of the then Liverpool boundary which is roughly the position of the depression/candidate eye discussed above. The section suggests that the top of the tunnel was 27.5 ft below the surface although it erroneously states the tunnel was 15 ft high (16 ft is more commonly accepted).

Fig: The relevant part of Telford's section courtesy of ICE and Liverpool & Manchester Railway Trust.

The Close

Fig: Schematic model built in OpenSim looking through the Crown Street gates towards Smithdown Lane at the top of the escarpment. Part of the surface has been made semi-transparent so that the eye and connecting passage can be seen. The tunnel can be seen at the bottom right. The tower is shown in grey and would not have been present at this time.

In the schematic I have interpreted the Close as being a cul-de-sac. Although the majority of notable parch marks oriented with known sidings, there was one curved mark that is not readily explained from known configurations of track and paths. While there may have been additional unknown features, it is also possible that it marks the location of the pathway into the close or alternatively was used during construction of the nearby tower.

Fig: The approximate position of the shaft highlighted on the OpenSim model

Conclusions

The tunnels from the Millers Close/Millfield and Mosslake Fields eyes met on 26 November 1827 and completion of the tunnel as a whole was reported to the board on 9 June 1828. At that stage the eye would have been superfluous and presumably backfilled and bricked up. It would be interesting to know whether there is any trace in the tunnel itself.

A case can be made for the depression seen in today's Crown Street park being the site of the original eye, albeit with its connection to the tunnel bricked up once it was no longer needed. Engineering Timelines suggests that the eyes were positioned south of the tunnel rather than north as here. However, a northerly location at Crown Street would afford a slightly shorter distance to the gates for removal of spoil.

The question then arises as to why the LNWR chose to ignore the eye rather than having it form the basis of the shaft for the ventilation tower. The answer here may be unique to Crown Street which by the end of the century had become a busy depot for coal and agricultural goods. Putting a tower in the centre of the plot would simply be too disruptive in terms of blocking track from the tunnels going to more distant parts of the site. The situation would be different at the other sites.

An alternative possibility alluded to by Thomas (1980) is that the depression was the result of a widely reported collpase of the tunnel due to use of too few props. However, it seems odd that it should have survived landscaping of the station and subsequently the park as well as being some distance from the tunnel itself.

If the depression could be proven to be the eye, it would form the sole surface feature presently visible in Crown Street that derives from the 1830 railway, albeit only from its construction phase. Even so it would be a testament to the courage of the men who built the first railway tunnel to pass under a major town and which played a significant role in the industrial revolution in the north-west of England. It also forms a valuable marker for the station itself.

Thanks to the Liverpool & Manchester Railway Trust for making available the tunnel tender document and tower plans

Last updated 23/04/19