The first recorded Liverpool address for Irish potter/poet Hugh Mulligan is on New Peters Street (later Peter Street) off Whitechapel where he lived between 1770 and 1774 (dates non-exclusive). Mulligan was an early mentor to William Roscoe and a member of a small set with anti-slavery views considered radical in a port based largely on the "African" trade.

Both terraced ends of the east side of Peter Street appear in Herdman paintings, the Whitechapel end merging into a row of shops and the other end capped by a pub and in the process of being demolished by Herdman's time.

The middle of the street, however, is not shown and I suspect that this area was occupied by an early form of court housing. As ever, a work in progress, much conjecture.

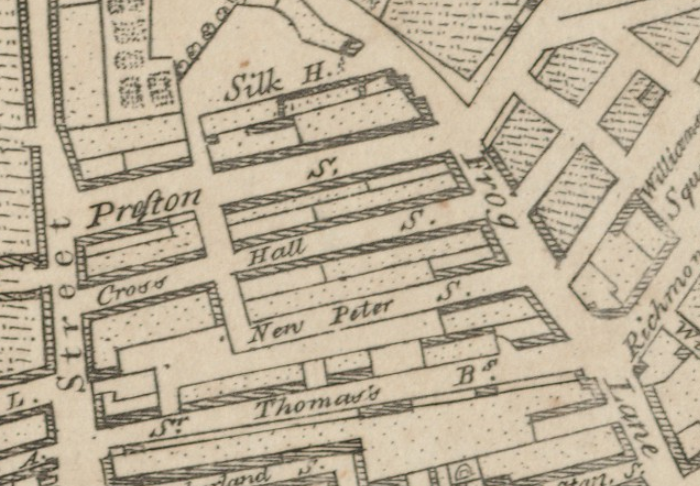

Fig: Williamson's 1766 map shows only the Frog Lane (Whitechapel) end of New Peter Street built out. North is to the left.

Peter Street

The origin of the name Peter Street is unclear. Nearby Stanley Street was named for the local Stanley family who owned the land and it is possible that the Peters family were likewise responsible for Peter(s) Street. The Peters family were wealthy merchants and Ralph Peters, who lived on John Street, became Town Clerk.

The first intimation of Peter Street appears on the 1766 map by Williamson on which it is laid out but only part-built. By 1769, however, both sides of Peter Street were built out and Horwood's map of 1803 shows in excess of 100 dwellings on or adjacent to Peter Street. It seems likely therefore that the house that Mulligan moved into was only a few years old.

Fig: Peter Street (left) as seen from corner of Dawson Street with the main thoroughfare of Whitechapel running left to right. Painted by WG Herdman in 1858. British Museum CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The street was demolished in the 1860s and the only visual record I have been able to locate comprises two watercolours by Herdman. In 1858 he painted a view of Whitechapel that included part of the south side of Peter Street and in 1867 a view of the opposite end of the street where it turned into Shaws Hill Street. The buildings are shown in the course of demolition although the corner pub is still occupied judging by the washing hanging across the street.

Both ends of the street show three-storey, single bay terraced housing with a narrow frontage although in at least one case there is a suggestion that two adjacent dwellings have been merged. There are also decorative additions to doors and at least one extra window.

The house seen in the course of demolition appears to extend back the full extent of the building. The visible doorway may be to the stairs and it is plausible that a wall once extended in line with it to form two rooms, front and back; if so, access to the back room would appear to be via the front. The stairway hints at the tight spiral staircase common at the time and observed at 10 Hockenhall Alley where it is at the right rear of a building with perhaps half the depth seen here.

Fig: Derelict court housing on Cross(e) Hall (Crosshall) Street. The front house was likely a back-to-back that has been extended while the back house abutted the back houses on the south side of Peter Street although it was built later. The Municipal Buildings on Dale Street can be seen in the background.

Some idea of the back houses on Peter Street may be obtained from a painting by Herdman of a partially demolished Crosse Hall (Crosshall) Street. This shows a full-size front house possibly extended at the rear and behind it a back house which is roughly half the depth of the standard front house. The back house may have been built after those on Peter Street (sometime between 1803 and 1835) and accordingly created a faux back-to-back not necessarily aligning with those to the rear off Peter Street.

Perry's 1769 street plan supports this view as it shows on the south side so-called back houses accessed via narrow alleys between front houses. Horwood's map suggests that the mid-street front houses were themselves small-footprint back-to-backs clustered in fours, two on the street, two facing the courtyard. Their appearance may have resembled the extant but now dilapidated house on Hockenhall Alley, three storeys with a single bay (Herdman view, internal photo, external photo, 1930s.

Fig: Grade II-listed No.10 Hockenhall Alley. Photo by Phil Nash from Historic England website.

Life in early court housing

While later courts had shared provision in terms of privies, ash cans and clothes washing, early courts may have replicated the general C18 century experience.

Water may have been obtained from a water carrier or from the Fall Well which was only finally closed in 1790. Clothes were traditionally washed and dried in the area now occupied by St John's Gardens, adjacent to the well.

Mains sewerage was almost certainly absent with nightsoil being collected, possibly from an earth midden though none is evident on the exterior.

Streets and courts in the OpenSim model have been left unpaved/flagged. Although Herdman shows Castle Street with pavements in 1786, it is not clear when side streets were addressed although they are shown in his later pictures of Peter Street.

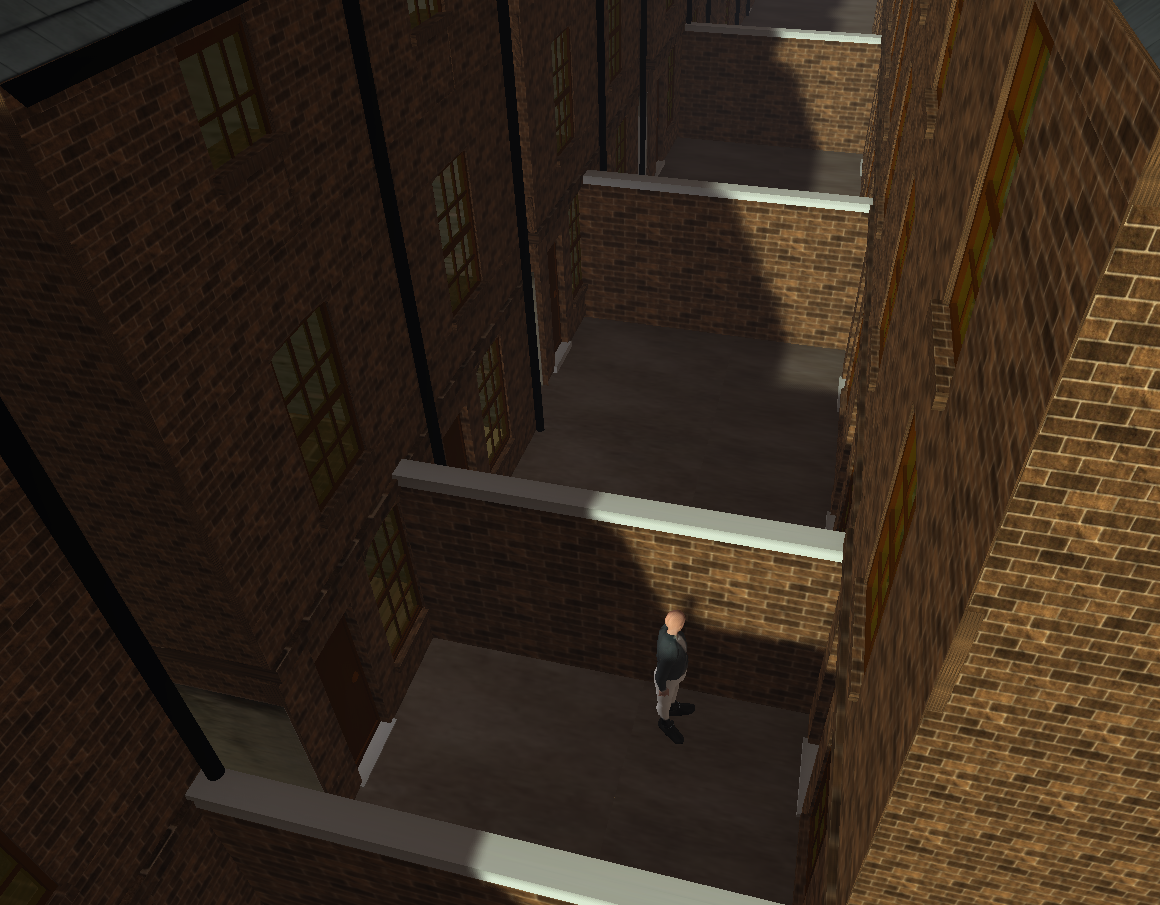

OpenSim build

Fig: Peter Street. A pub can be seen at the far end on the corner of Shaw's Hill Street. To the right is a narrow access to one of the courts via the limewashed alleyway.

Fig: The first court off Peter Street appears to have had only two dwellings facing one another.

Perry's map shows walls delineating four courts containing a total of six back houses. These may have varied in size with some larger than the basic unit (slightly larger than 3x3 m) located at the rear of the first court (as seen from Whitechapel).

This raises an interesting possibility, namely that the back houses may have been of interest to those running micro-businesses from home. The court may have provided some storage or work space and larger houses would have additional rooms for small-scale enterprise, albeit cramped. Stewart observes that work carried out in the court by the likes of oakum pickers often contributed to their run-down state. Taylor similarly suggests that cellars may have been sub-let not only as living space but for "people following trades."

By contrast the other side of Peter Street was more conventionally built with few back-to-backs and back houses. Court construction was a largely speculative enterprise and it may be that the landowner decided on a limited trial in the first instance until a viable market was demonstrated. Stewart cites returns of the order of 10% per annum.

With the downturn in the pottery business Mulligan may have become self-employed with a room in one of the larger back houses which he dedicated to pottery decoration and copperplate engraving. That said, there are other outhouses on Perry's map that might have been a smallscale business workshop or, of course, Mulligan may have worked elsewhere as he did at the pottery on Brownlow Hill and perhaps subsequently when it moved to Park Lane.

Later developments

Later courts would typically have 3-4 houses on either side of the yard space with a water pump and shared provision in terms of privies, ash cans and washing. None of this is apparent on Perry's map although this could simply be a matter of resolution. They are visible to a degree on Gage's map of 1835.

Fig: By 1835 there are small buildings in the courts that probably represent privies etc. There are also additional courts, house extensions and other developments to the rear. The alleys leading to the courts may have been built over to give the tunnel entrance characteristic of many courts.

Residents and reputation

Those living on Peter Street in the 1770s appear to have had diverse occupations drawn from groups including mariners, artisans and labourers but not, for example, merchants. This was low-cost housing for those required to live close to their work in the centre of town. Among the artisans was at least one further potter (Scarisbrick) as well as one or more of weavers, joiners, bricklayers, ropemakers, shoemakers/cordwainers, sail makers, shipwrights and watchmakers. There was at least one shopkeeper, a tobacconist, but his shop or kiosk may have been elsewhere.

Over time, however, the street (and others nearby) gained a poor reputation, Hume's map of 1858 identifying it as an area of "crime and immorality". Densely populated with lodging houses as well as courts, it featured periodically in lurid news stories involving murder, violence against children and dog-fighting.

Whether this trend started much earlier and contributed to Mulligan's decision to cross Whitechapel and live in nearby Charles Street is unknown. As Elizabeth Stewart notes in her recent book Courts & Alleys, it is unwise to generalise on the condition of court properties or the experiences of their occupants.

Around this time Mulligan dropped the designation "potter" from his entry in Gore's directory so another possibility is that his aspirations in that direction had run their course and Charles Street seemed a better fit for the future.

Demolition

As well as perhaps being an early example of court housing, Peter Street was also among the first to be demolished despite the apparent absence of the infamous cellar dwellings (Taylor seems to suggest that there were some in the vicinity but not a uniform distribution). This presumably came about as a result of bye-laws in Liverpool's Sanitary Amendment Act of 1864 which, in the face of recurring cholera outbreaks, introduced new building regulations and powers of compulsory purchase for demolition of slum properties.

In 1867 the Medical Officer of Health, Dr William Trench, recommended demolition of 387 houses to counter the threat of typhus and cholera. This correlates with the date of Herdman's watercolour. While the cholera map of 1866 suggests that there were fatalities on Peter Street, the number was not on a par with other areas of the town.

It is of possible interest that Herdman seems to have only recorded the area from within as it underwent demolition. Perhaps Peter Street was a place he preferred not to linger in when populated but a place he felt deserved to be recorded for posterity even as a shadow of its former self.

Much of the site is now occupied by the 1872 Midland Railway Goods Office by Sumners & Culshaw latterly converted into a Conservation Centre. The destruction of inner city housing in favour of railway developments was a commonplace event in Victorian Britain. What happened to the displaced residents is largely unrecorded.

Fig: The former Midland Railway Goods Office. Peter Street is to its left, Crosshall Street to its right.

Further info

Stewart. Courts and Alleys

Taylor. The Court and Cellar Dwelling: the Eighteenth Century Origin of the Liverpool Slum