George Stephenson's 1830 map of Liverpool Crown Street shows a building opposite what would later become the yard of the Grand Junction Railway. This, however, is not a railway property but rather the Railway Inn, an early example of a building that would soon become commonplace in towns and cities across the country.

As ever, a work in progress, much conjecture…

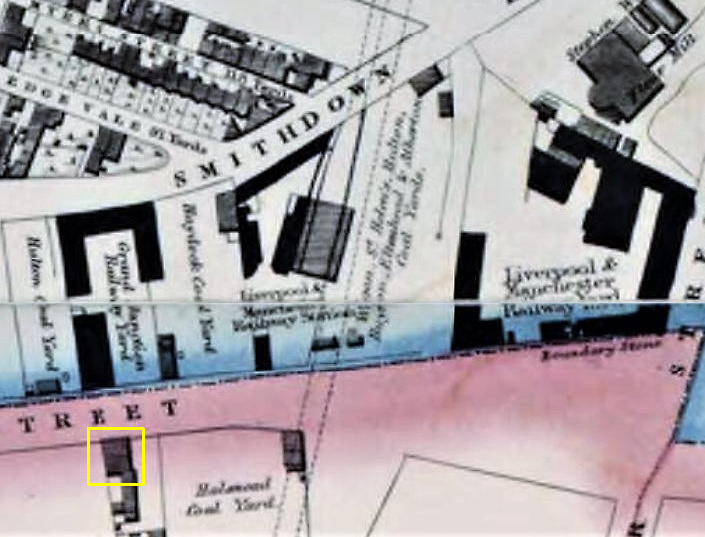

Fig: Michael Gage's map published in 1836 showing Crown Street expanding with yards to the north (left on the map) and the site of the Railway Inn highlighted in yellow.

Notwithstanding temperance sensibilities among the directors, local breweries were often quick to exploit the arrival of railway travellers and workers as at Patricroft. However, little seems to be known of Crown Street's equivalent, the Railway Inn, apart from the brief entry and 1904-dated photo in Freddy O'Connor's book "A Pub on Every Corner: South Liverpool".

Although a building is shown on the site on the 1830 map, the earliest building labelled Railway Inn is on the 1849 Town Map. It is assumed that the inn changed neither name nor location in the meantime.

Most of the images in the book (and pubs on Crown Street) derive from a chain owned by the brewer Peter Walker & Son. However, Walker only arrived in Liverpool from Ayr in 1836 so cannot have been the original owner if, indeed, the company later acquired the inn.

History of the parcel

Likewise the ownership of the parcel is unclear although it seems to have been entirely separate from the station and ran through to Olive Street, named for the nearby Botanic Garden. The Garden gradually migrated to Edge Lane to avoid pollution from the Crown Street yards and re-opened there in 1836.

Swire's 1824 map shows the parcel as directly adjacent to the Garden and apparently non-agricultural, perhaps cleared for building although it pre-dates the laying-down of Olive Street itself. There is an outside possibility, however, that it formed a carriage park for visitors to the Garden. Indeed, the land may have been owned by the Garden and parcels sold off to part-fund its running expenses, ultimately including the move to Edge Lane.

Adverts appeared in local newspapers around this time for land close to the Crown Street yard and the inn may have been one outcome. However, it does not feature in reporting about the opening day (15th September 1830) so it is also possible that it opened subsequently.

Opening day accounts generally mention the William IV Hotel whose proprietor, a Mr Harding, provided a grandstand with musical accompaniment. However, there was a King William IV hotel in Williamson Square and it seems not unlikely that this establishment sponsored the grandstand rather than one local to the station.

Stephenson's map suggests that the inn was among the first buildings on the parcel in 1830 although 1829 Gore's directory lists a Lightfoot court off Olive Street. However, there was in fact another Olive Street off Back Russell Street. This makes it difficult to unambiguously identify residents on the Crown Street parcel(s). However, one possible Olive Street resident was Thomas Rogers whose (highly pertinent) occupation was given as gardener. It is also possible that Stephenson's map was selective given that it fails to show the dominant building in the vicinity, Stephen White's windmill.

By 1836 the inn had been joined on its narrow parcel by a range of other buildings running through to Olive Street. Some were contiguous with the inn and may have been livery stables for those using the inn, for rail travellers or for those working in or visiting the yards. There was also a house or business on Olive Street itself. Mid-century much of the parcel was redeveloped to form a court-style housing project called Barton's Buildings (also known as Court No.2), albeit with an unusual pattern comprising clusters of four houses with a square rather than rectangular layout. By the turn of the century, however, much of the parcel was vacant apart from the Crown Street frontage.

An early proprietor of the inn may have been Samuel Hunter. His wife, Jane Hunter, remarries in 1839 to John Taubman following the death of her husband the previous year. She was the owner of the inn at the time and her new husband was a joiners' foreman in Gray's yard, part of the railway station.

Whether they kept the inn going is unclear although it may have been a struggle as the Liverpool Albion in 1842 carries an advert announcing an auction of the premises, goodwill, fixtures and fittings.

The inn disappears from records sometime before 1912 and is not visible in an aerial view of 1934. Of the street directories available online, it appears only in the 1860 Gore's (street number: 236, proprietor: Samuel Hancock) but earlier editions may not have listed establishments on the outskirts of town.

Other businesses on the west side of Crown Street

Unlike the east side, the west side of Crown Street does not appear to have developed incrementally. Although the parcel was vacant in 1830, Gage's map shows the Halsnead coalyard on the corner of Crown Street and Myrtle Street South by 1836. The Halsnead colliery was served by the Willis branch just west of Huyton Quarry station. This probably opened in 1834, presumably at roughly the same time as the yard at Crown Street.

It seems likely that the Halsnead yard had rail access across Crown Street from its opening although presumably the line was worked by horses. Horses rarely feature in what little artwork of Crown Street survives other than in pulling road carriages. However, most of the coalyards had two buildings, one for offices, the other stables with nearby midden, and horses likely played a major role in shunting as well as off-site coal deliveries.

The only other western parcel shown as occupied on Gage's 1836 map was an oil works. This has two small buildings and whether manufacture or distribution took place there is unclear. The precise nature of the product being handled is unclear but the nearby railway would potentially have been a significant customer for lubricants in particular.

The appearance of the inn

Fig: The Railway Inn on Crown Street after the photo in O'Connor's book. There was probably a flight of stairs on the right that led down to an area at basement level, possibly staff accommodation. This is no longer present in the 1904 photo although the tops of the windows overlooking the area are still visible. Vaults may have been accessed via a passageway to the left.

The inn is perhaps a little more architecturally interesting than the average street corner pub of this era. This may fit with it serving both pub and hotel functions as with a traditional coaching inn. With the offset door it has what Murchison (pdf) calls a "shop" format. The giant pilasters are reminiscent of the Custom House Hotel; unfortunately the photo is truncated vertically so it is impossible to state what order (if any) they had, nor whether there were any further decorative elements above.

Although much else differs, pilasters are also seen in the former Marble Hall Hotel at 68 Vauxhall Road, more recently the Marble Hall Cafe. This was a Threlfall's pub, the brewery opening on Crosbie Street in 1818 adjacent to what would become the Wapping Goods station. The hotel in its present form does not appear on maps, however, until post-1860s.

Whether the clock on the Railway Inn was an original feature is unclear; perhaps the idea was that travellers would immediately see that they had time for a drink before their train departed.

Business development

Inns played a key role in coaching and, indeed, in the early days of the Stockton & Darlington Railway which opened in 1825. However, by 1870 builder and former Liverpool mayor Samuel Holme was bemoaning the absence of good inns in many towns and ascribed it to the replacement of road coaches by railways. Those that survived were often less hotel, more public bar.

Unsurprisingly, railside taverns like Patricroft sought to ply passengers and staff on passing trains with food and drink, something the directors were anxious to avoid. Drunkenness among railway employees was a significant concern for the L&MR and the basis of a number of accident reports and disciplinary procedures.

By the 1870s railway hotels at mainline stations would become large and ornate. In 1830, however, the Railway Inn was notably less elaborate in appearance than the Mayfair (Kean's) Hotel on the corner of Tabley Street and Park Lane. Kean's (as it was more commonly known) was supposedly built to cater for rail travellers alighting at Wapping which, of course, turned out to be exclusively a goods station.

The end of passenger services at Crown Street in 1836 likely had significant consequences for the residential functions of the Railway Inn. However, even prior to that hotels in the centre of Liverpool were touting for business outside the station and provided their own transport into town.

There was one category of potential user that would persist, however, namely train crews who would need to stay at Crown Street overnight. However, in most cases these were likely accommodated in quarters above company offices.

While the station provided waiting-rooms, they did not provide food or drink beyond the services of a freelance orange-seller. Many would bring their own picnic basket but even so the inn must have been an attractive proposition to those whose departure was delayed.

With the closure and demolition of the passenger station and a switch to livestock (briefly) and coal, the inn was unfavourably situated in an industrial setting. There were works springing up in the vicinity with potentially thirsty staff to assuage but equally there were likely more handily placed public houses. One possibility is that at this stage the Railway Inn may have catered more to the needs of colliery agents and railway middle management wanting to socialise or entertain for business purposes.

According to Thomas (1980), William Hulton was obliged to apologise to the railway directors when in 1846 his agent at Edge Hill was seen to treat a large number of enginemen at "Mr Vidler's Hotel", i.e. the Tunnel Hotel. This anecdote, possibly linked to an upcoming election, illustrates use of the hotel by agents (and presumably coal merchants) as well as highlighting the dim view taken by the railway of such activity by its operations staff.

Nevertheless, both establishments must have turned some profit to have survived as long as they did (although vacant for some time, Kean's was demolished only relatively recently). In due course, however, there was considerable competition on and beyond Crown Street and this may ultimately have sealed the fate of the Railway Inn.