Liverpool's cultural development during the latter part of the eighteenth century was greatly influenced by William Roscoe. Roscoe, however, was famously of relatively humble origins, his father at the time of Roscoe's birth being an innkeeper. Leaving school at 12 to work in his father's market garden, Roscoe would later acknowledge the role played by an early mentor, Hugh Mulligan, in introducing him to the arts. Indeed, Mulligan is credited as an influence in the biography of Roscoe written shortly after his death by his son Henry.

Very much a work in progress…

Mulligan is often mentioned in passing as a somewhat enigmatic Irish poet who was by trade a painter of pottery and a copperplate engraver. He was employed by the china works on Brownlow Hill owned by James Pennington. The works backed onto a bowling-green behind the inn on Mount Pleasant run by Roscoe's father, the New Bowling-Green Inn.

Fig: Although the area was a little more developed by the time of this map (Gore's, 1790), the two bowling-greens on Mount Pleasant and associated inns are still evident as are the market gardens at the bottom of the hill. The U-shaped Brownlow Hill china works can be seen behind the lower bowling-green along with the windmill used for grinding colours although by this time the works had closed.

Pennington moved the business to Park Lane in 1767/8. Whether Mulligan moved with it is unclear. The manufacture of ceramics for the most part declined in Liverpool (the Herculaneum Pottery was for a time the exception) although the decoration of pottery manufactured elsewhere continued. During his formative years, however, Roscoe in his spare time could go to the nearby china works and there he acquired the basics of painting from Mulligan.

The Irish poet (nicknamed Mully or Little Mully, presumably a reference to his stature) may also be the subject of a verse in Roscoe's poem Mount Pleasant written at this time. If so, it suggests that Mulligan was an excellent performer of his poetry and perhaps more generally a popular raconteur. Roscoe wrote the poem when he was 16 although it was published much later in 1777. It is notable for verses directed against the slave trade and the greed it engendered. These were radical and potentially dangerous ideas to hold in Liverpool at this time, thoughts that Roscoe and Mulligan likely shared with a select circle.

Fig: Verse from Roscoe's poem Mount Pleasant possibly referring to "Mully" alias Mulligan.

Giving up working his father's market garden, Roscoe now briefly tried his hand at bookselling before becoming apprenticed to an attorney. When he qualified in 1770, his spare time was used to further the arts in Liverpool, a town very much focused on commerce and in particular the slave (or "African") trade.

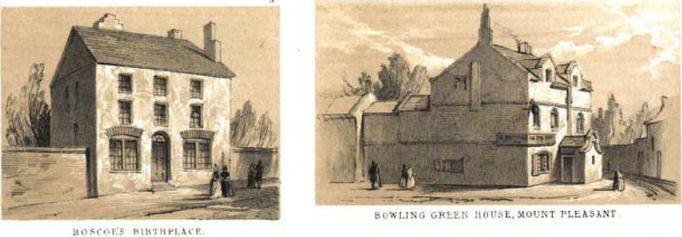

Fig: Convention has it that here were two Bowling Green Inns owned by Roscoe's father on Mount Pleasant. This image from Herdman's Pictorial Relics has them mis-labelled from this conventional standpoint although Herdman claims in a footnote that his interpretation is correct. Convention conversely has it that Roscoe was born in the one on the right in 1753 but his family moved to the one on the left a year later.

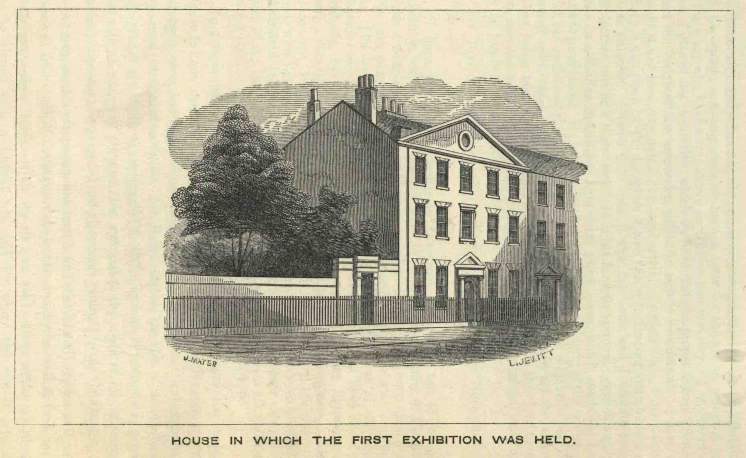

By now a relatively wealthy attorney, Roscoe played a leading role in organising the Society for Artists in Liverpool (pdf). Although short-lived, the society organised the first provincial art exhibition in the country. It was held in in 1784 in Roscoe's new house on Rodney Street (one of the earliest in that road and still extant). While Roscoe contributed two sketches, his early tutor Mulligan is notable by his absence.

Fig: Roscoe's house, setting for the first exhibition (from the article by Mayer).

The early radical circle encompassing Roscoe and Mulligan may also have included the Irish-born clergyman and author George Gregory who lived briefly in Liverpool and later wrote to his friend Roscoe on 12th Feb 1801 asking that a guinea be given on his behalf to "poor Mulligan."

Where Roscoe had prospered, Mulligan had not.

Mulligan's travails

Mulligan appears to have had at least six children and the dates of their premature deaths allow Mulligan's location to be approximated via parish records. Thus he lived on (New) Peter(s) Street between 1770-1774 and then at 3 Charles Street 1778-1785 (dates non-exclusive). The children (Ann, Thomas, George, James, Sarah, Elizabeth) were buried by their father in the graveyard at nearby St John's (formerly behind St George's Hall). The identity of their mother, however, is unclear.

A somewhat cryptic inscription on the Mulligan portrait (see below) alludes to one Sarah Granger as being "dulcinea to his Fable Knight of La Mancha". However, the idealised Dulcinea described by Cervantes was the object of Don Quixote's unrequited love and her reality in any case far removed from his vision.

A woman called Sarah Wright was married to labourer James Granger at St John's church in 1790 although there is no necessary connection to Mulligan.

An outside possibility is that the famously benevolent Mulligan was somehow acting in loco parentis for children of women who for one reason or another could not bury them. The mortality rate for infants was notoriously high in some areas of Liverpool.

Fig: Map of central Liverpool published by Gore 1790 showing Peter and Charles Street either side of the diagonal street labelled White(chapel) with St John's at the top.

From around 1780 onwards the blind poet Edward Rushton began composing radical verse and around 1792 opened a bookshop on nearby Paradise Street. He would become an important member of Roscoe's circle.

Around this time Mulligan was similarly a bookseller on Whitechapel and in 1788-1789 he co-published a newspaper with Rushton, the Liverpool & Lancashire Weekly Herald. Mulligan appears to have closed the paper in response to a visit by naval officers following a piece by Rushton critical of the activities of the press gang.

Nevertheless the two remained friends and Rushton would later compose an elegy to Mulligan and his 1806 ode To a Bald-headed Poetical Friend may be similarly directed. Mulligan likewise used Rushton as the lightly anonymised subject of one of his poems "Epistle to Mr. E R".

Mulligan published a book of anti-slavery poems in 1788 possibly following Roscoe's lead. It received mixed reviews but remains of academic interest. Around this time Mulligan is listed as a copperplate engraver at 3 Charles Street in 1790 Gore's directory to which is added bookselling in 1796 and 1800.

The later elegies by Roscoe and Rushton among others are testament to Mulligan's enduring popularity despite what had become parlous financial circumstances and possibly failing mental and physical health. In 1794 he may have acted as witness at the marriage of Samuel Moore, a painter, and Mary Page.

Final days

For whatever reason Mulligan in his latter days appears to have been taken under Roscoe's wing. Presumably he had no other family to care for him and was almost, if not completely, destitute.

In 1798 a letter from Roscoe to his wife mis-dated 31st April mentions that "little Mully" was found walking in the gardens at Allerton (just prior to Roscoe's removal there from Birchfield). Mulligan was well pleased with the situation and, rubbing his hands, said "Well, well, this will be the place for quietness."

Roscoe's concern regarding Mulligan was shared by his son William Stanley who on 17th March 1798 wrote to his father that "poor Mulligan is very ill."

In 1801 William Stanley writes from Oxford enquiring of his mother whether Mulligan has yet been translated to the Dingles (sic), then a beauty spot on the Mersey where the Roscoes had a house. In the absence of a reply the question is repeated on 17th Jan 1802. Mulligan died on 9th December 1802.

Frog Lane in Mulligan's day

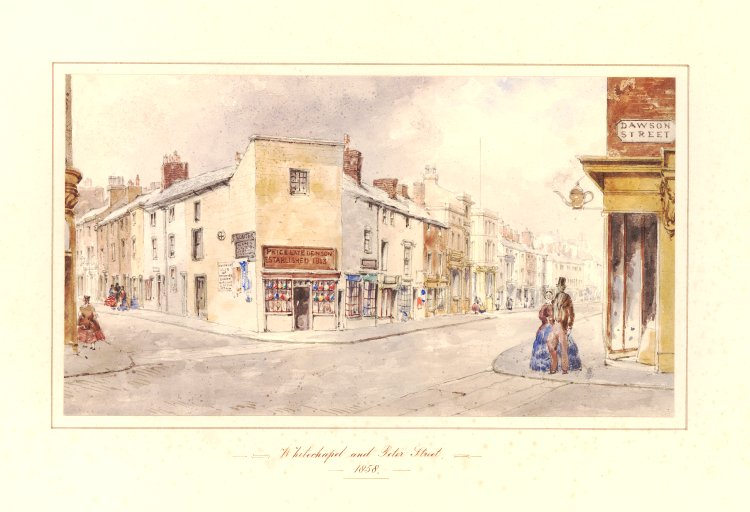

Mulligan lived on New Peter Street (as shown in the 1769 Perry map, presumably to distinguish it from Old Peter Street which became Peter and then School Lane) which at the time ran off Frog Lane (later Whitechapel) halfway towards Dale Street before forking hard right into Shaw's Hill Street. Although there are houses running the length of the street, Perry's map suggests that there were narrow alleyways leading to a second row of interstitial houses, possibly an early version of court housing or alternatively workshops. Although Peter Street these days is dominated by the rear of the former Midland Railways Goods Office, it may have been largely residential in 1769.

Both Peter and Charles Streets opened onto Whitechapel, formerly Frog Lane. This represented the upper reaches of the creek that represented the outfall of the stream from Mosslake Fields and which ended in the pool. The area seems to have been prone to flooding and conditions in cellar dwellings in particular must have been dire. Herdman produced a small sketch of shops in Whitechapel during a flood.

Peter Street had terraced housing at either end and Herdman painted one during demolition c.1860, showing that there was a public house on the corner with Shaw Hill Street (blocked off by this time).

Herdman twice painted the shops adjacent to Peter Street as seen from the opposite corner of Dawson Street and one shows the terrace at the Whitechapel end of Peter Street. The shop at the end of the street has a characteristic chamfered corner, possibly a later modification, that can be seen in a more distant view reproduced in Kay Parrot's book of Herdman paintings.

Somewhat earlier, around 1830, Brierley sketched a row of shops opposite Dawson Street, presumably on the other side of Peter Street.

In 1769 at the time of the Perry map there were still a few open fields off Whitechapel. However, there were also signs of industry. There was a (probably rather noxious) tanyard close to the (Old) Haymarket and a silk house off Preston Street. Sir Thomas Buildings (now Sir Thomas Street) had a coalyard, foundry and distillery.

Fig: Shops on Whitechapel with the mainly residential Peter Street branching off on the left. Image courtesy of British Museum licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Perspective

Both Roscoe and Rushton suffered hard times, Rushton losing his sight early in life on a slaving voyage and Roscoe latterly becoming a bankrupt. Each, however, had periods of success and posterity has been kinder to them than poor Mully who, personal and business vicissitudes notwithstanding, remained true to himself and perhaps paid the price accordingly.

We learn more of this radical yet benevolent man from Rushton's elegy. Mayer also quotes an elegy written by a mutual friend, possibly Liverpool printer John McCreery.

The Roscoes were given a posthumous portrait of Mulligan by the artist, Julius Caesar Ibettson, described as "disguised" but "like". The unusual headgear probably derives from a voyage the two made from Hull to Leith to meet Thomas Vernon, a bookseller who went bankrupt in the late 1780s but later became Liverpool's first auctioneer. Ibettson describes Mulligan as a "fellow sufferer" on Vernon's "Scotch campaign" and suggests that they had ended up as a fairly desperate street theatre act with Vernon as showman, Ibbetson a dancing bear and his son and Mully monkeys.

The long clay pipe shown in the portrait, however, was a favourite pastime of Mulligan's. Whether a plantation crop was ultimately a comfort to or the death of Mully remains a mystery.

Acknowledgements: Part of the narrative derives from summaries of letters written by or to William Roscoe and available from Liverpool City Archives.