On 4th May 1844 the first train of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway (L&MR) entered the new Manchester terminus at Hunt's Bank. The station was situated between a workhouse and a cemetery and approached by road up an incline from Great Ducie Street. The train entered via a bridge across the Irwell having traversed Salford on a raised viaduct in part alongside the Manchester & Bolton Railway. The train itself was dressed with flags but this was the only outward sign of celebration. The same day Manchester Liverpool Road, the former passenger terminus, became exclusively a goods station.

Fig: The refreshment room of the original station forms the first storey of the block by the red bins. An additional bay was later added to the left of the original five as well as the second storey.

In fact, Victoria station (as it had become known after a suggestion by a shareholder) had been open since 1st January but only to trains of the Manchester & Leeds Railway (M&LR) Company, the company that had built and still owned the station. Previously the company had used a station just over a mile to the east at Miles Platting (Oldham Road) and, while that station also went over to goods, many of the company administrative functions remained there as well.

As ever, a work-in-progress and some conjecture…

(Belatedly, I discovered a digitised album of plans which have yet to be incorporated).

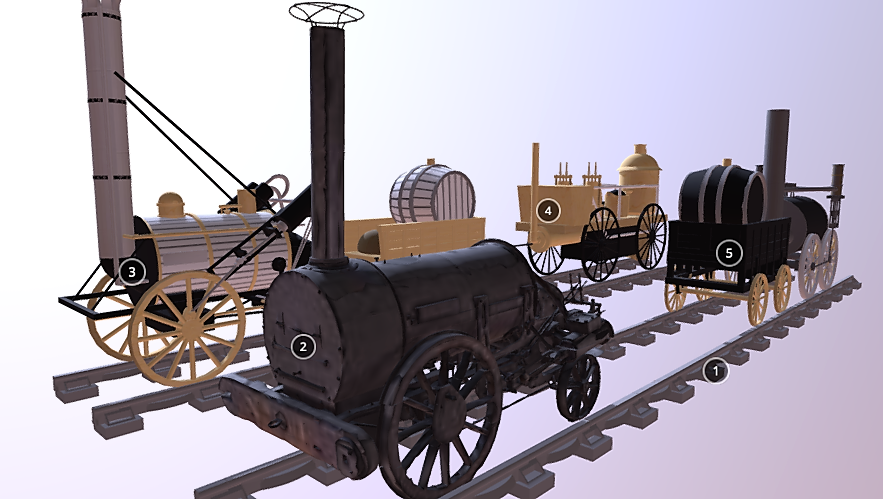

The inclined plane

The M&LR extension west from Miles Platting to Victoria involved a gradient and trains were to be worked into Victoria by a stationary engine that powered a continuous rope haulage system. Trains would be led into the station by a pilot wagon attached to the rope. On departure for Leeds the pilot would be coupled to the rear of trains leaving the station down the incline with the rope providing additional braking during the gravity run in addition to the brake on the pilot itself. Note, however, that the gradient reversed subsequently with the rope pulling the train up into the station at Miles Platting.

The system was coordinated between the two stations by telegraph. However, rope haulage was not working at the time of Victoria station's opening and, as was often the case, banking locomotives were frequently used instead.

The station

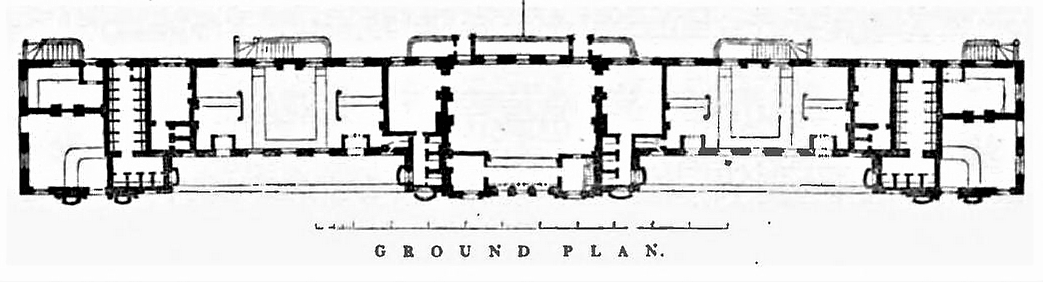

Victoria was owned by the M&LR but as with many large termini or stations at junctions was shared with other companies, including in this case the L&MR. Indeed, the plans published in The Builder are symmetrical about the shared refreshment room with the M&LR occupying the eastern half towards Leeds and the L&MR the western half towards Liverpool. The central refreshment room was operated independently by the restauranteur Vantini & Morigy (the former also managed the North Euston Hotel at Fleetwood).

Fig: Plans published in The Builder for Liverpool Victoria station. The refreshment room is central and moving out from there in either direction (and speculating) there is the first and second class Ladies' Waiting Room, Booking Hall (one side for first and second class, the other for third class), general Ladies' Waiting Room, i.e. third class, Gentlemens Lavatories (first and second class), and in the wing pavillions a parcels office and superintendent's office. Third class and staff facilities were provided in the basement accessed via area steps on the platform.

The station architect was the Principal Engineer of the M&LR, none other than George Stephenson who had, of course, previously acted in a similar capacity for the L&MR. The primary responsibility, however, fell on his assistant from those Liverpool days, Thomas Longridge Gooch, and it is plausible that Gooch or his assistants carried out much of the detailed design.

Unlike Crown Street, plans for Victoria apparently exist in the Greater Manchester Archives and the station has been the subject of an eponymous book by Tony Wray. While I have yet to hunt these down, Wray has compiled a useful archive regarding the LYR (pdf) which deals in passing with the early days of Victoria station.

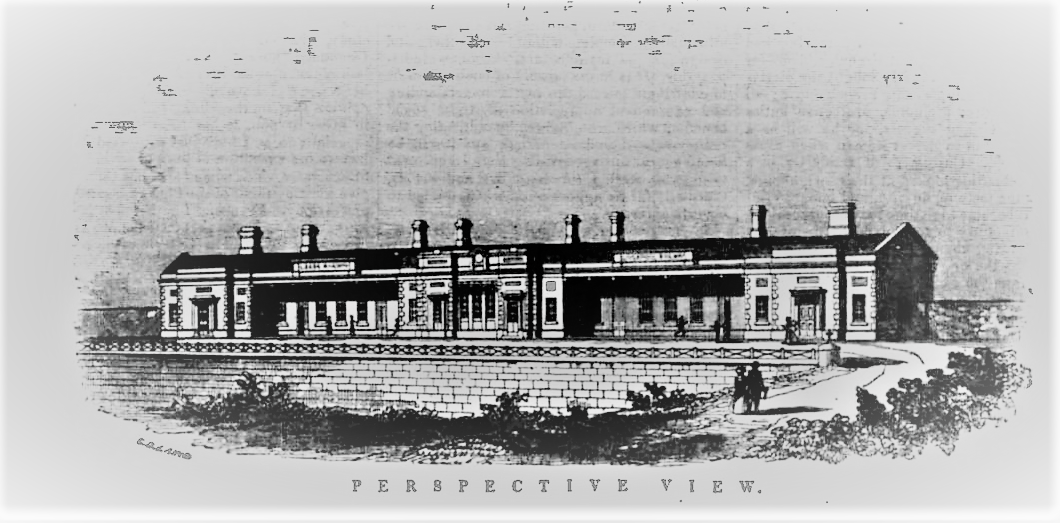

The visual record

The external appearance of the original station is recorded in The Builder. There are several early images, including one by Kirkham apparently made on behalf of the contractor Thomas Brogden.

In 1845 AF Tait produced a series of high quality views of the M&LR that included the interior and exterior of the station that will be mentioned subsequently. A view by CW Clennell shows two small lodges to the east that govern access to a street carriage park and loading bay. There is also an extension, most likely the telegraph office governing the inclined plane.

Fig: The exterior of Victoria station as depicted in The Builder. Hunt's Bank runs down on the left where a staircase was later provided for LNWR passengers as a shortcut.

Little of the original station exists apart from a somewhat modified refreshment room now used by staff. Originally it was a single storey and five bays wide. An additional bay may have been added later at the same time as the second storey. The third class refreshment room and staff facilities in the basement may also persist in some fashion?

Destination boards can be seen on the canopy above the booking offices in Tait's print of the exterior: Derby, Leeds, Selby and Hull are evident with others besides.

The Booking Halls

The twin Booking Halls again have a symmetrical layout with an office space bounded by a counter on either side running the width of the building, one for third class passengers and the other for first and second class. Each counter had its own entrance from the street and exit onto the platform with an additional counter facing the passengers on entry at right angles to the other. This may have been an attempt to separate processing of passengers on arrival (a waylist of passenger names was normally compiled) from advance booking. First and second class passengers may also have had their luggage collected at this stage for stowing on the roof; third class carriages had no roof storage and passengers received no assistance from porters. The relatively narrow space between the two counters may have regulated access to the platform.

However, the term Booking Hall in this case may have been something of a misnomer. The M&LR started limited service in 1839 and was, after the Newcastle & Carlisle, the first to adopt the standard cardboard ticketing system devised by Thomas Edmondson (pdf). This provided better accountability and faster processing by use of pre-printed tickets that were simply stamped with the date before use. According to Thomas (1980), the opening of the "Leeds Junction line" led to the use of such tickets on the Liverpool-Manchester line by the L&MR in May and the following month across its entire network.

A map from 1850 suggests that the arrangements shown in The Builder for the Booking Halls were subsequently modified.

Connecting Liverpool and Hull by rail

A continuous service between Hull and Manchester Oldham Road had been available since 1841 via trains operated by George Hudson's York & North Midland Railway. Determining the nature of the final link to Liverpool was, however, a protracted business given the often varying interests of railway companies, town councils, businessmen and populace more generally.

When the line beween two of England's premier ports finally opened in 1844, the track was owned by multiple companies. As we have seen, from Liverpool to Manchester employed the L&MR and from Manchester to Leeds Hunslet Lane the M&LR, albeit running on track owned by the North Midland Railway from Normanton to Leeds. Leeds to Hull was accomplished in two hops via the Leeds & Selby Railway and the Hull & Selby Railway, the terminus in Hull being at Manor House Street railway station adjacent to the Humber Dock.

Prior to the opening of Manchester Victoria, passengers would have needed to take a cab or omnibus from Manchester Liverpool Road to the M&LR station at Miles Platting. Even when Manchester Victoria opened passengers initially had to change trains there to complete the next stage of the journey to Leeds. However, pressure from passengers eventually told and through running of trains was negotiated.

The significance of the connection

The journey from Hull to Liverpool would later become a major route for mass emigration from Scandinavia, Germany and the Baltic states to America. However, in 1844 numbers making the crossing were relatively small, probably of the order of one thousand. However, in time the route would prove immensely useful for export of cotton goods from Manchester to the continent via Hull as well as of woollen goods from the West Riding to the Americas via Liverpool.

The interior and rolling stock

Tait's interior view shows five lines but only one platform albeit of roughly conventional height. Passengers were not expected to cross the lines and trains were accordingly worked from the single platform, albeit augmented by an additional bay for local services embedded in the platform at either end.

The lines were connected by a series of turnplates, including two sets adjacent to the refreshment room. This apparent redundancy may mark the limits of the two jurisdictions but they may also reflect the minor change in track gauge between the two companies (4ft 8.5in on the L&MR vs 4ft 9in on the M&LR).

Several carriage types can be seen in Tait's interior view. To the left at the platform is what appears to be a relatively conventional first class carriage, painted yellow with coupe windows so probably belonging to the L&MR. Porters can be seen handling luggage still stored on the roof although there is no evidence of external seating for a guard.

On the third line to the right is a mixed train of what appear to be first class carriages and third class "Stanhope"-style wagons.

On the remaining two tracks we can see a rake of brown coaches in the distance (later LYR livery was teak and subsequently brown) and a rather curious rake of what might be first class cabriolet-style coaches in which the end compartments are optionally open, perhaps intended for summer use. These are yellow so presumably L&MR. The fact that L&MR rolling-stock occupies the eastern end of the shed and putative M&LR the western suggests that observance of the demarcation at the centre of the station was pragmatic.

There were additional sidings external to the northern wall accessed via a series of turnplates.

After the opening

In a short time, however, both companies would merge into larger groupings, the M&LR into the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway (LYR), the L&MR into the London & North Western Railway (LNWR). The LNWR appears to have been much less relaxed about having to use a station owned by a rival concern and in 1884 would establish its own station, Manchester Exchange, to the immediate east of Victoria and sharing one platform, the longest in Europe.

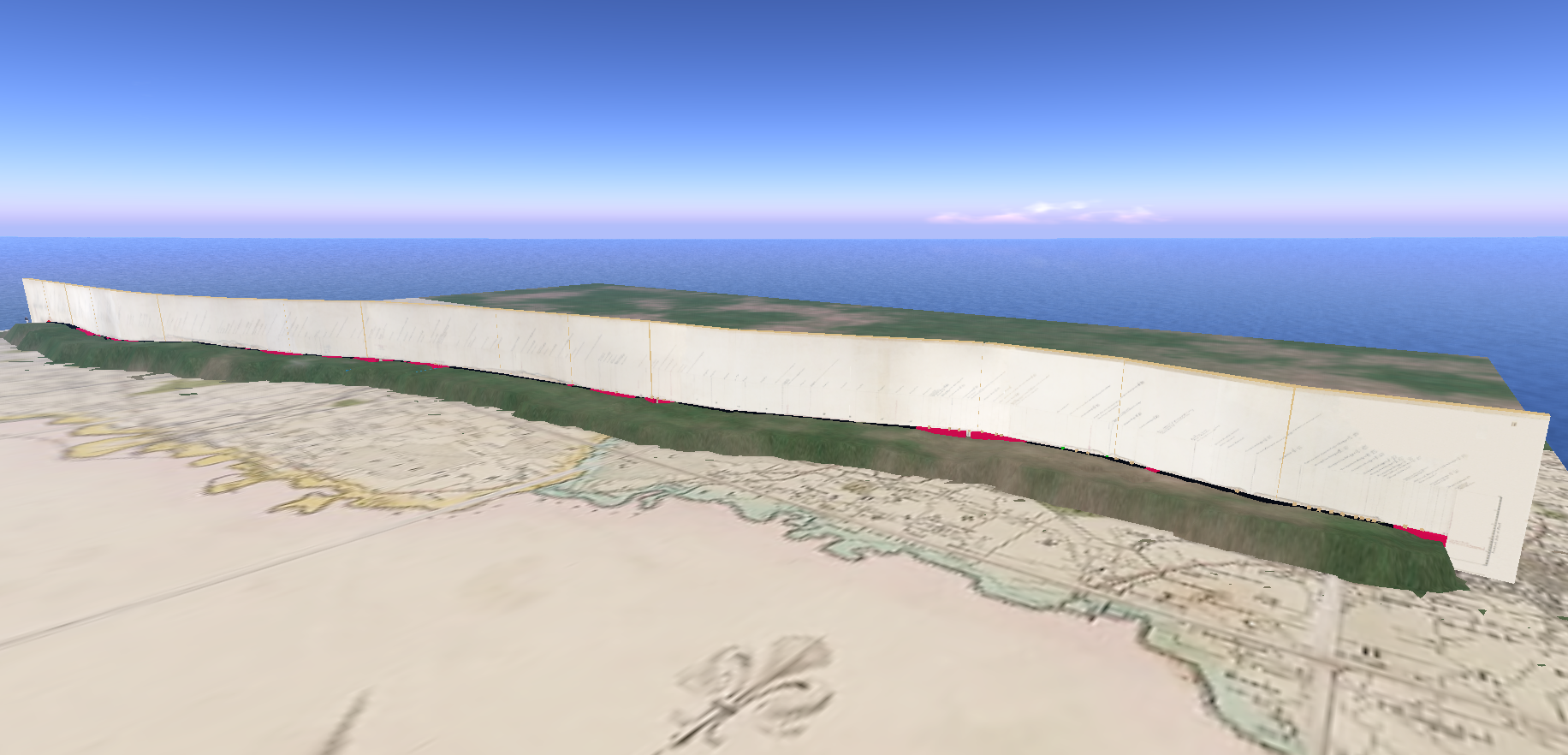

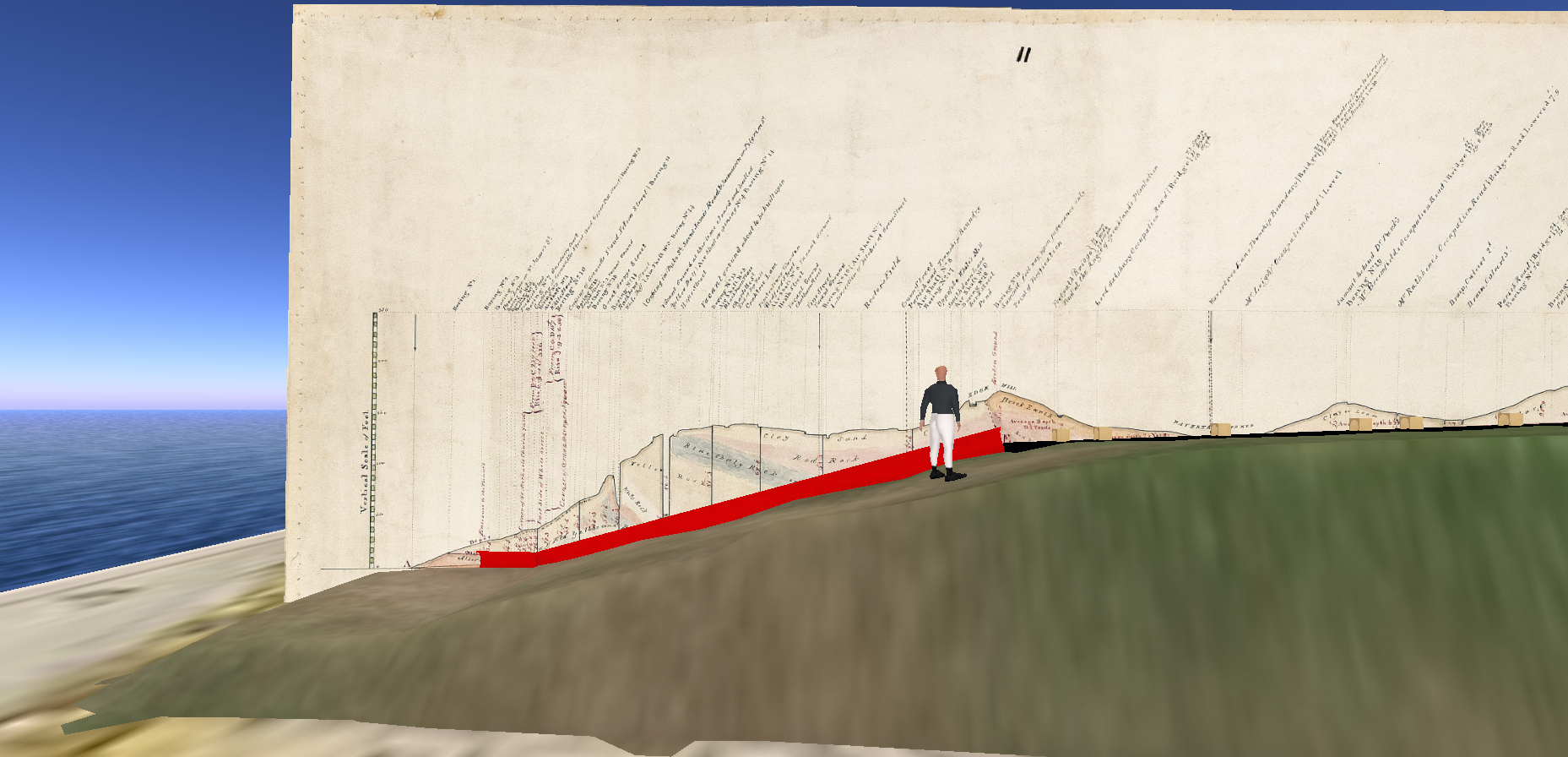

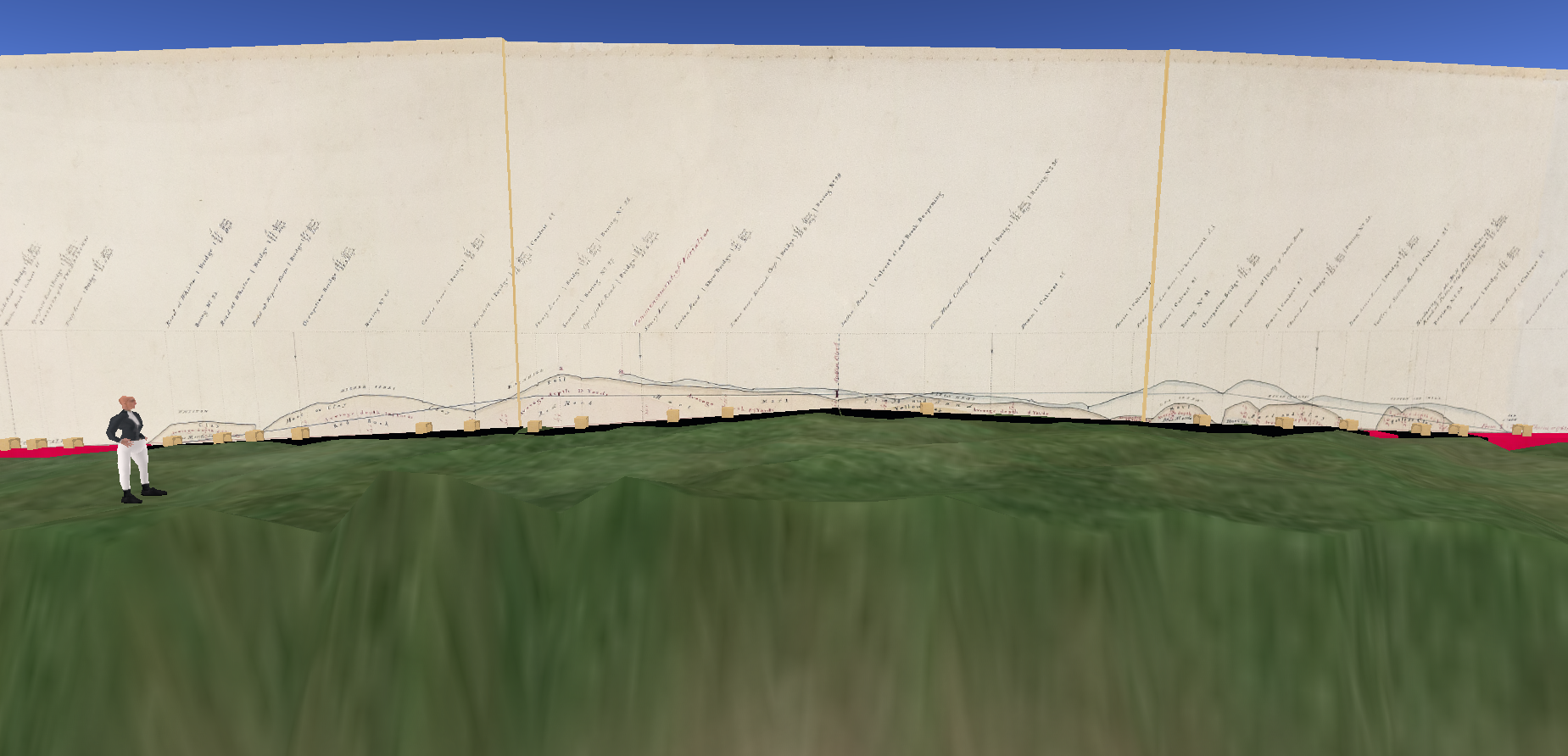

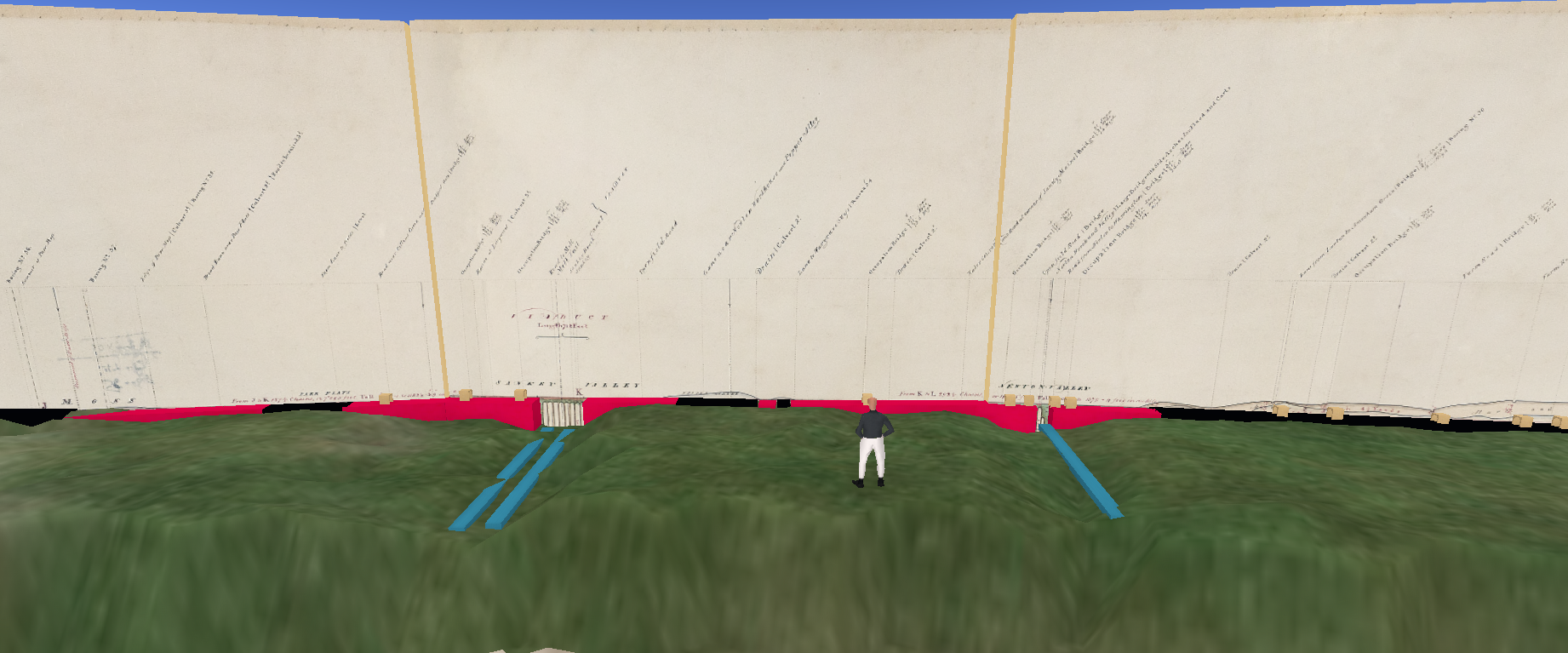

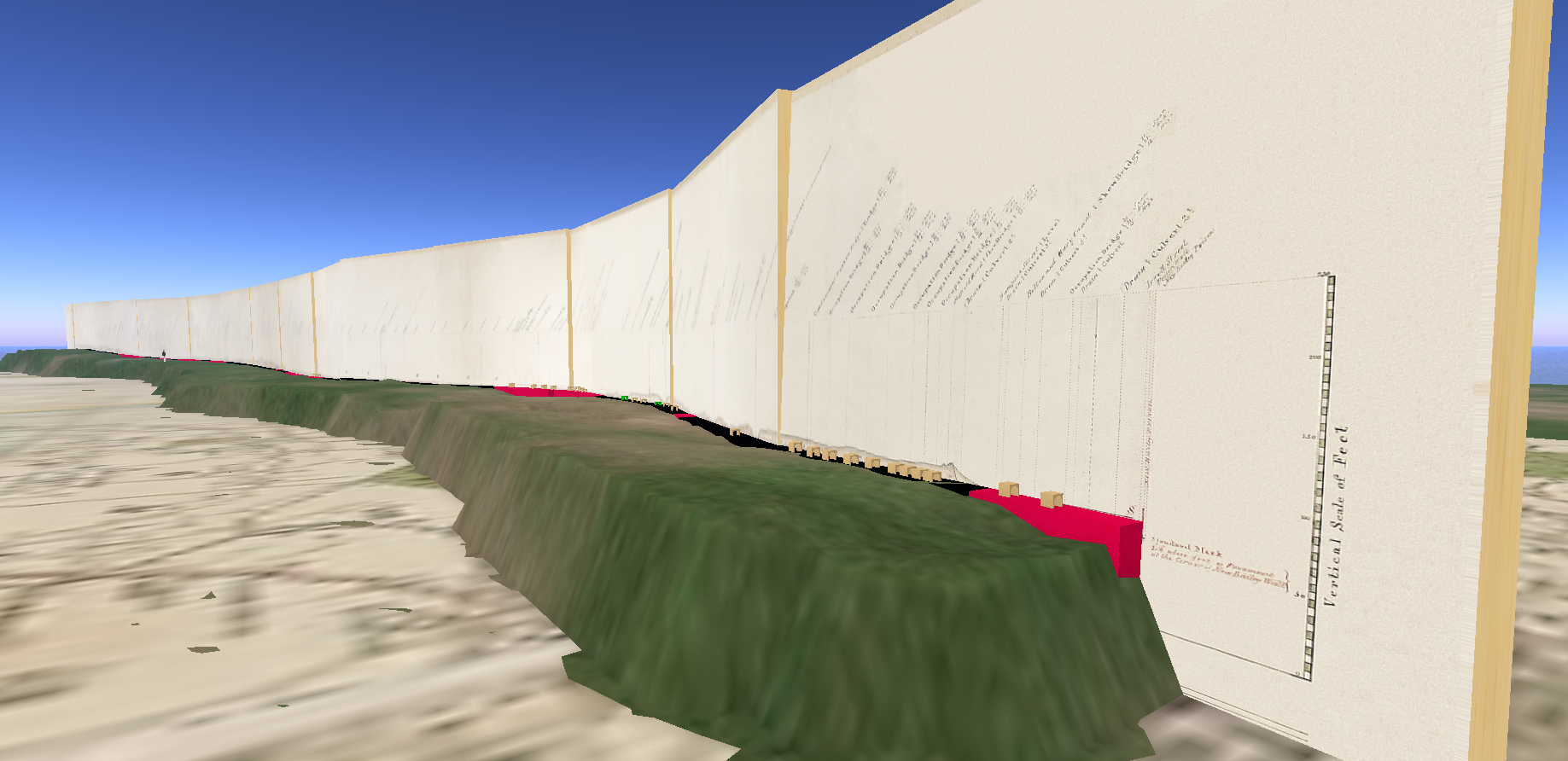

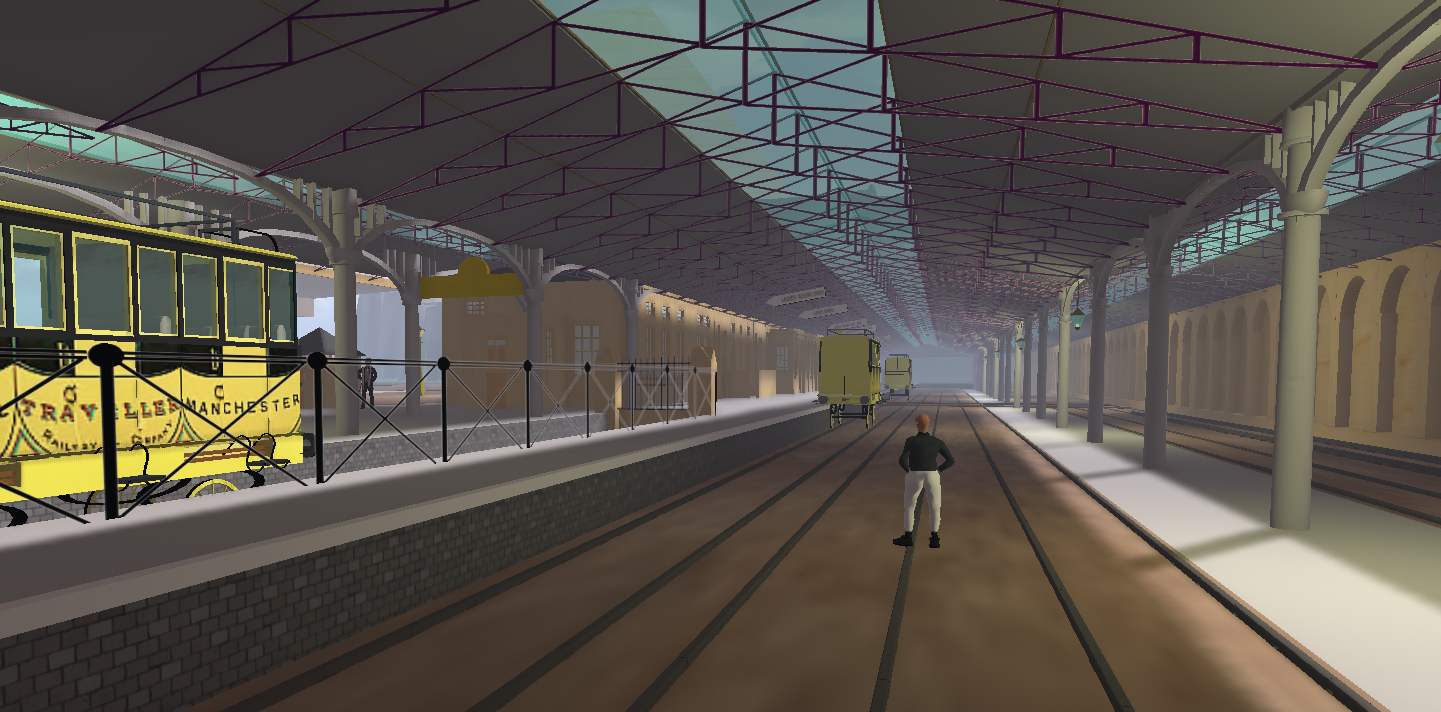

The OpenSim model

The OpenSim model attempts to replicate the views presented by AF Tait in his 1845 publication. It differs in some respects from the outline plans, notably in the projection of the refreshment room onto the platform. Tait also plays down the presence of a bay inserted into the platform for use by local rather than through services. Although several sources refer to a bounding wall on the south as well as north side, it does not appear in any of the images and is hence omitted. The windows, doors and staircases on the platform are a work-in-progress. There is no evidence of tackle associated with the inclined plane, possibly because it was no longer used, so this is omitted.

Fig: Exterior seen from Hunt's Bank Approach off Great Ducie Street. L&MR station is to the left, M&LR to the right.

Fig: Interior of Manchester Victoria looking west towards Liverpool.