Introduction

There are many accounts of events at Parkside that led to the death of Liverpool MP William Huskisson on the opening day of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in 1830. They are typically incomplete or erroneous and there is no reason to suppose that this one is any different. However, it takes as its starting-point a different perspective, by no means original but commonly omitted, that only one engine out of the eight actually took on water at Parkside itself. I've updated this account after having read The Liverpool & Manchester Railway by RHG Thomas which adds some interesting sidelights. Please bear in mind that I draw largely but selectively from secondary sources.

Brandreth's view

Dr Joseph Pilkington Brandreth was a physician who worked at the Liverpool Dispensary on Church Street founded by his father to provide medical advice and treatment to the poor1. His brother Thomas was a solicitor and both brothers were listed as proprietors in the Railway's enabling act. Thomas is probably best remembered, however, for his horse-driven entry to the Rainhill Trials, Cycloped. The two brothers lived next to one another at 43 and 45 Rodney Street.

Brandreth's recollections were recorded in a letter to his sister Mary who had married the MP Benjamin Gaskell and now lived in Yorkshire.

Brandreth was in the last row of seats at the back of the leading train on the northern line which was drawn by the engine Phoenix. According to most reports (but not this one) it would have picked up coal and water at Parkside before moving away and waiting for the other trains to catchup.

Brandreth might be expected to make a good witness given his academic background and affiliation with the company. However, his testimony does not start too well as he gets the number of trains and passengers significantly wrong. To be fair, there are few accounts of that day that appear completely reliable.

Getting out of his carriage and climbing to the top of the cutting, Brandreth looked back and saw "two trains arrive, and stop at their purpose place" but the fourth (this number including Phoenix) remained beside the Duke's carriage. This observation is odd because those two trains should have been drawn by North Star and Rocket which might (erroneously) suggest that it was the next engine, Dart, that was involved in the accident and hence stopped at Parkside.

The multiple watering places

One point uncommonly made by Brandreth but confirmed by Rolt and Thomas among others concerns multiple "watering places". Contrary to many accounts, most engines took on water and fuel at points distant from Parkside itself, presumably to speed matters up by using a parallel rather than serial approach. The details are unclear but we know that Phoenix was about 880 yards from Parkside and that Rocket should have been at 440 yards which suggests that the interval being used was 220 yards and that North Star and Dart were therefore scheduled to halt at 660 and 220 yards past Parkside respectively. If no train was scheduled for Parkside itself (it would have entailed unseemly proximity to the ducal train), then Comet would have been at -220, Arrow at -440 and Meteor at -660 yards.

At a total of 1540 yards, this is patently much less than the 1.5 mile (2640 yard) distribution cited by Rolt who implies an interval of 440 yards. This might suggest that the interval is either incorrect or variable.

However, if four trains with an interval of 220 yards were stationed beyond Parkside and three with an interval of 440 yards before it, the last train would be rather handily stopped at Newton-le-Willows and the total distance would be 1.25 miles or 2200 yards. In that case a delay between the fourth and fifth trains would be expected and the egress of the passengers might have reflected a miscalculation or misapprehension on their part as to when the delay was likely to occur.

A further possibility is that the last four trains would use the same locations as those presently occupied beyond Parkside, the three leading trains starting out as soon as the fourth arrived in place, the latter shuffling up to the position occupied by Phoenix before starting to take on water. This strategy would seem to allow better continuity for the review at Parkside.

Presumably the pause also allowed the engines to gather steam after having their boilers topped up with cold water. The water cranes dispensing pre-heated water at the actual station had not been installed by this time so this would also apply to Northumbrian.

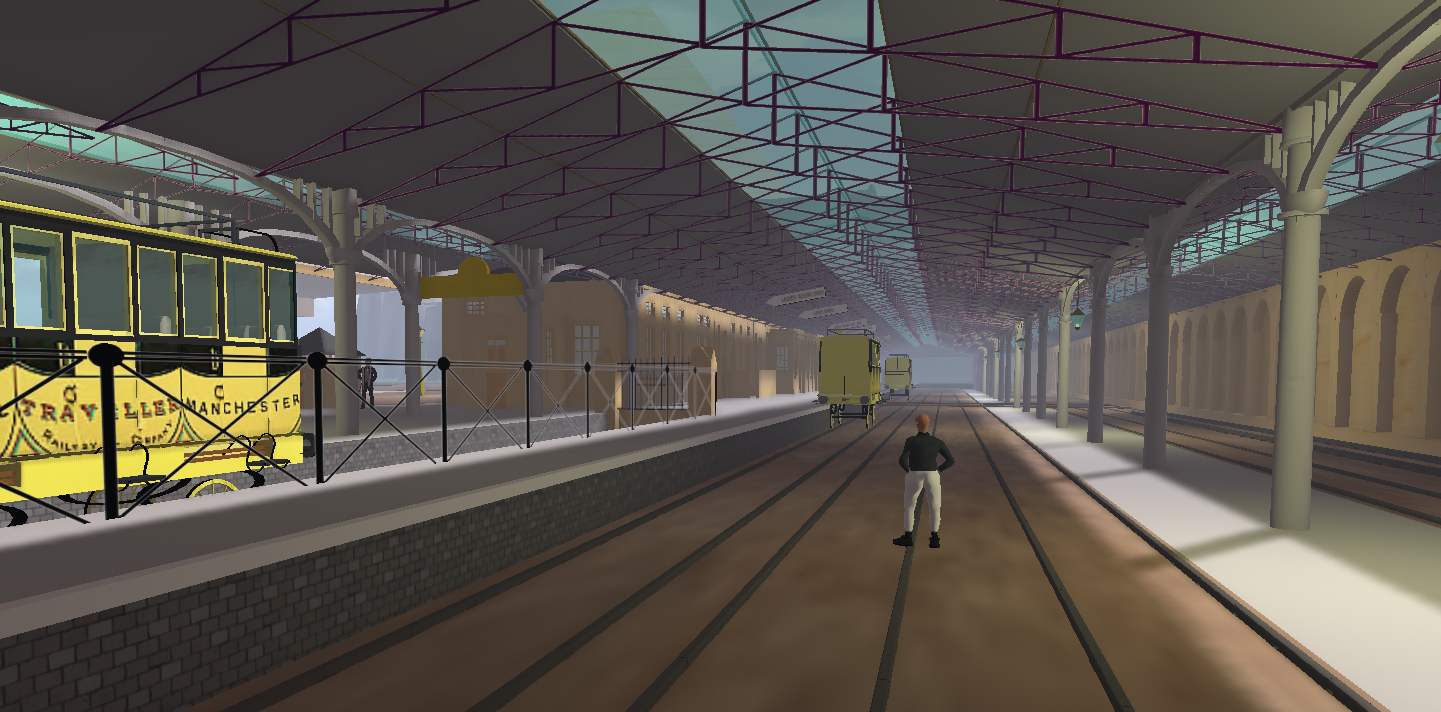

The review

The parade was subject to review by the ducal train first at Rainhill and now at Parkside. This piece of theatre was for the entertainment both of the other passengers desirous of seeing the ducal train and, of course, the myriad spectators, many of whom had paid for a seat in a grandstand. Several journals mention that not only did the trains pass by slowly but that they also reversed and ran past again, doubtless with the intention of providing a more prolonged spectacle for the crowds. This latter manoeuvre does not appear in the orders to engine men and likely reflects high spirits on the day among the engineers acting as train directors. It must, however, have been a major concern for the policemen managing traffic in the two stopping places.

The overall context, that this was a review, explains why Rocket was seeking to run through the station, albeit slowly, rather than stopping, its "watering-place" being on the far side. The fact that ultimately it did pass through with minimal delay is explained simply by the need to make space to recover Huskisson once he was removed from the track. Dart, the next engine, was presumably halted short of the accident site, policemen with speaking-trumpets having run back up the line to warn oncoming trains which would have had to run on some distance both to brake safely and to avoid collision.

Coincidentally, there have been a couple of claims made against Dart (controlled by Gooch) as recounted by Ferneyhough2, including the entry for Huskisson in the Dictionary of National Biography. The scenario presented here might give some basis for a possible misunderstanding.

Fearing the delay to the fourth train (Dart) indicated some serious incident, Brandreth left Phoenix and began to walk towards Parkside only to be met by a Mr Forsyth (presumably Thomas Forsyth, another of the early proprietors) who had run to fetch him. Together they returned to Parkside where Brandreth found the mortally injured Huskisson on a door (as makeshift stretcher) being treated by the Earl of Wilton who had applied a tourniquet to the leg (Wilton was not medically qualified but had a considerable interest in anatomy). Wilton would be the main witness at the hastily convened inquest the next day at which the company was completely exonerated.

We now turn to earlier events prior to arriving at Parkside and then at Parkside itself.

Huskisson

William Huskisson was not the first railway fatality but he is probably remembered as the most prominent. He became one of Liverpool's two MPs in 1823 and did much to promote the cause of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in Parliament despite coming from the landed classes and having an interest in the canals. A moderate Tory, he had held a number of significant government positions including President of the Board of Trade but tendered his resignation from government in 1828 when the Lords blocked electoral reform. According to Huskisson, the ultra-Tory Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, was not supposed to accept the resignation but to use it as a bargaining chip with the Lords. It was not to be and his departure from government was arguably a significant loss. While possessing no great oratorical skills and, indeed, being somewhat reserved if amiable, Huskisson was an astute politician who reflected the spirit of the times in much better fashion than the deeply unpopular Wellington. Severe illness in August 1830 meant that Huskisson was incapable of fighting his seat in person in the election but he was in any case returned safely through the machinations of his Liverpool supporters. He received a rapturous welcome when he subsequently visited the Liverpool Exchange in advance of the railway's opening.

The ducal train

The principal guest, however, was the Duke of Wellington who came to Liverpool to open the Railway on 15th September 1830. Together with more than 700 guests he undertook the inaugural 31 mile rail journey from Liverpool to Manchester.

Wellington's ornate ducal carriage and associated cars were being pulled by the powerful steam engine Northumbrian under the control of Principal Engineer George Stephenson. The ducal train ran freely on the southern line while the remaining seven trains used the adjacent northern one. This meant that the VIP train under Stephenson's supervision could vary its speed, review the other trains so their passengers could see the Duke and pause at features of special interest without impeding traffic on the adjacent line. I suspect it also gave Stephenson the opportunity to liaise with the other drivers and would facilitate the rapid extraction of the VIPs in case of need. As we have seen, the trains on the northern line were supposedly separated by about 200 yards, a relatively short distance if one remembers that a train travelling at 15 mph covers 220 yards in 30 seconds.

Arrival at Parkside and an unscheduled promenade

The engines necessarily stopped to take on water and replenish fuel at Parkside, the halfway point, passengers having been specifically asked not to get out of the carriages during this wait. Although the proceedings thus far had not been without incident3, the Directors must have been feeling a certain degree of elation that things had passed off so well and perhaps they dropped their guard. Again, as had earlier occurred at Rainhill, there was an opportunity for the Duke to acknowledge the passengers in the other trains once more as they slowly ran past the ducal train, albeit largely for the benefit of the doubtless considerable crowds. This was, after all, to some extent a repeat performance.

Politically the Duke may have seen the ceremonial aspect of the journey, the parades at Rainhill and Parkside, as an opportunity to impress on both locals and national newspapers his support for some of the country's most powerful technologists and "merchant princes". The entirely positive response he was receiving from the crowds in and beyond Liverpool must have been some vindication. The railway company would in turn be hoping for some implicit endorsement of their product, reflected lustre and a positive review for subsequent projects.

Northumbian was first to Parkside and then saw Phoenix and North Star slow and pass through to their watering-places. Rocket was due next. However, one after another acccompanying dignitaries began to dismount from the train and to stretch their legs at Parkside while they waited for their engine to be serviced and the others to pass.

Estimates of the number of passengers dismounting vary; some say around 15 (at least, initially), others 50 (the ducal train had one or two additional VIP carriages carrying Directors and their guests as well as a car for the band). The men were reportedly mingling and chatting, doubtless in high spirits and looking to the future. The women stayed onboard, either following instructions or because of the absence of steps from the carriage. The policemen apparently attempted to persuade passengers to return to their seats but were in an awkward position given the presence of their superiors. In any event, they were likely significantly distracted from monitoring other areas.

The layout and atmosphere at Parkside

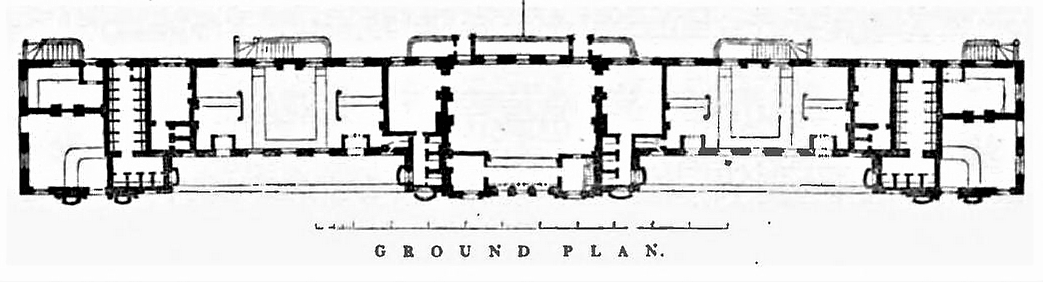

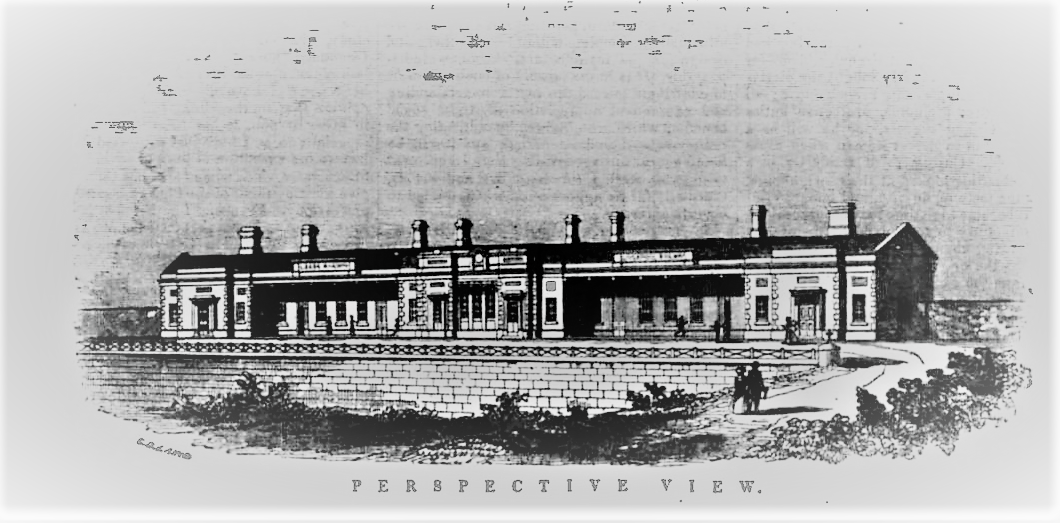

The layout of Parkside is reasonably well-documented by the works of Bury and Shaw, the two artists most associated with the early days of the railway. Parkside was located in a relatively shallow but steep-sided cutting with, on the north side, small water reservoirs behind a fence (referred to as "pools" or "puddles" in some descriptions). Contemporary accounts, however, suggest that the reservoir was at that time in the process of excavation and some 15 feet deep. There are some suggestions that the hut seen in many pictures was added in 1831 although the door that later served as a stretcher was expropriated from one of the nearby company "hovels" so buildings were present, either associated with railway construction or for use as stores. Presumably the steep slope of the cutting extended a little further towards the excavation if the hut was absent. The picture shows water cranes opposite one another on either side of the track and on the southern side a boiler and steam engine to pump pre-heated water to them.

(Update 13/09/17) Bury's picture shows a relatively mature Parkside layout with the addition of a shed for a spare engine not seen in the first version. However, the rather dishevelled hut shown may have been replaced by 1834 (possibly in 1831) with a much nicer single-storey building with a hipped roof and a dropped-edge hood moulding over the window, a motif common to several of the company's works (there is an image in the catalogue to the London exhibition termed The Padorama). However, Thomas includes a sketch map by EJ Littleton that suggests a far more primitive layout at the time of the opening with water on both sides of the track rather than solely behind the fence to the left. In that case there were probably no boiler, engine or water cranes although these must have been built soon after to have appeared in Shaw and Bury's prints. The suggestion is that stone had been quarried on both sides of the track and the ravines thus created had both filled with water.

We know little of the crowds present from nearby towns and villages but the bridge closeby and the fields above the cutting would both have formed natural grandstands close to trains and VIPs alike. The intervals between the passage of trains would be filled by music played by the band accompanying the ducal train. We know that there were also significant crowds at Eccles where the injured Huskisson would later be taken and some have suggested that the crowd at Parkside gave first warning of the imminent arrival of Rocket some 200 yards away.

Rocket

All the engines were under the command of one of the senior engineers although it seems likely that there were regular drivers in attendance as well. Joseph Locke was in charge of the Rocket but Thomas identifies Mark Wakefield as driver and Adam Hodgson as Director of the train. He also names two brakesmen; although the engine may have lacked brakes, presumably some of the carriages did not. The firemen are not identified for any train and also notably unnamed for Rocket only is the flagman. Altogether, the picture emerges of a busy footplate with some potential conflicts of responsibility. Indeed, there are (marginally fanciful) pictures showing Northumbrian with up to seven people, most in top hats, crammed onto the tender and footplate on the opening run.

(Update 13/09/17) Thomas includes a copy of Stephenson's instructions to "engine men" that requires they carry three flags: white (meaning "go on"), red ("go slowly") and purple ("stop"). Presumably these were intended for dismounted guards to communicate with other trains in the event of a derailment or similar incident. However, there was also a signal flag carried by the train (possibly by the guard) which when upright indicated that the train carrying it should proceed and if horizontal "must be considered a signal for the next engine to fall back or come forward, as may be required", a somewhat disconcerting ambiguity.

Rocket was pulling the third train on the northern track. Although winner of the Rainhill Trials the previous year, it was now relatively elderly and, although heavily modified, out-classed by more recent designs. Accordingly, it was pulling a shorter train and was running late into Parkside. It seems not unlikely that it would have slowed in particular on the ascent of the Whiston incline, doubtless slowing the trains behind as well.

(Update 13/09/17) Rocket may also have been delayed by the derailing involving Phoenix and the subsequent minor collision with the following train worked by North Star. The location is not stated but distances between trains were supposed to be 100 yards at slow speeds and 200 yards above 12 mph. Given the collision, the distances were clearly the bare minimum and arguably inadequate.

The Northumbrian's passengers descend

Huskisson had most likely been travelling towards the rear of the ducal carriage and sat separately from both his wife, the latter joining a group of other women, and Wellington. After dismounting at Parkside, he chatted with Director Joseph Sandars and, possibly at the bidding of Chief Whip William Holmes MP, had shaken hands with Wellington, either to be civil or, according to others, to start some kind of rapprochement. Wellington was seated at the forward end of the ducal carriage and to one side, presumably at this stage the side nearest the passing trains he would be expected to acknowledge. Whether Sandars had debarked simply to chat or to encourage a return to the carriages is unclear. Doubtless policemen would be reluctant to enforce company policy if a Director was among those on or between the tracks. It is worth mentioning that the surface of the permanent way would have been close to the level of the rail and there were no sleepers to trip over.

The ducal carriage was sandwiched between two cars for the use of the Directors, their guests and lesser notables and preceded by the band wagon (which is presumably not counted in the sum of three carriages officially drawn by Northumbrian) and tender.

The ducal carriage was 32 feet long and 8 feet wide with 8 wheels. It had only one entrance on each side and lacked built-in steps, a staircase intended for the benefit of lady passengers being hooked up at the rear and not deployed (presumably the dignitaries jumped or lowered themselves down to exit at Parkside). It would be challenging for Huskisson to gain entry without the assistance of those steps.

Huskisson had suffered a strangury at the recent funeral of George IV and the remedial surgery by Copeland had paralysed one leg and numbed part of the other. His attendance at the railway's opening had therefore been in considerable doubt. Walking would have been difficult for him but doubtless lifted by the occasion and proud of the achievements of his constituents, he was determined to participate.

It is hard to imagine what the passengers who descended onto the track had in mind. Having seen Phoenix and North Star pass through, they must have been aware that the majority of trains had yet to arrive and certainly those adjacent to the northern track will have seen how close was the approach of the passing train. They must also have gathered that the other engines were in fact being watered elsewhere. Parkside was a replenishment stop only for Northumbrian.

Walking on the track had been encouraged at some of the "open house" company events held to popularise the railway and it is possible the dignitaries could see passengers disembarking from the stationary North Star and Phoenix further up the line. Those with seats facing trackside (the seating for 30 ran down the middle of the ducal carriage) may have wished to have a better view, dismounted on that side and walked round the engine only dimly aware of the safety issues. Some of the elderly gentlemen, not least Huskisson at 60, may also have sought the opportunity for a "comfort stop". Finally, it is also possible that Rocket's late running had been noted by those on Northumbrian earlier. These were men who had made careers and fortunes from their ability to establish a relationship at a propitious moment that would later lead to a deal. Perhaps this was too good a chance to miss.

Rocket is seen approaching

According to Edward Littleton, the Duke terminated the conversation with Huskisson with the words "Well we seem to be preparing to go on - I think you had better get in". This erroneous statement was presumably precipitated by excitement in the crowd due to the imminent arrival of Rocket, then some 200 yards distant and presumably slowing for the review as it passed the ducal carriage. This may have precipitated the first movement towards the carriages as a means of escape rather than departure as the Duke surmised, unable to see Rocket.

If one assumes that the alert was given at 220 yards and Rocket was travelling at 15 mph then there was an interval of 30 seconds between alarm and impact. Of course, Rocket was most likely already slowing for review so the interval may have been nearer 60 or 90 seconds, sufficient time to consider multiple options.

Huskisson was presumably aware that Rocket was not scheduled to stop. His first reaction would doubtless have been to follow Wellington's advice and clamber aboard the ducal carriage via the door midway along and in the direction of the oncoming Rocket. In the absence of the deployable stairs the 38 year-old Edward Littleton did this with no little difficulty and then pulled Prince Esterhazy up after him. Holmes was also in the vicinity, possibly with one other, and Huskisson may have decided that being at the back of this apparent queue was not the best option for him.

Space around and beyond the train

There are suggestions that Huskisson crossed the adjacent track with a view to harbouring there or clambering up the bank but the presence of the excavations may have limited the available space to climb.

One can roughly estimate the likely minimum overall width of the railway cutting by looking at aerial photos of the Sankey and Newton viaducts which are both about 24 feet across. We know that the distance between the rails was standard gauge, 4 feet 8.5 inches, and, indeed, that the ducal carriage was some 8 feet wide, implying an overhang on either side of about 20 inches. The width of Rocket's train is unclear (several different types of carriage were in use that day) though the overhang was probably much less (some say just 6 inches). However, if we assume it is also 8 feet and the clearance 18 inches, then the clear space at the trackside would be at least 3 feet 3 inches, probably more. This would certainly have been sufficient to accommodate Huskisson if he crossed the track although whether he was in a position to make that judgement is unclear. The presence of the excavated pit and associated works, fence, etc may have complicated matters and we do not know to what extent any space was already occupied by passengers and local dignitaries..

The distance between the two middle rails, sometimes called the "six foot", is contentious with estimates ranging from 4 feet to standard gauge, the attractive but possibly apocryphal idea being that wide loads could be carried down the centre pair of rails. It is not especially relevant to the discussion here.

There may also have been a subliminal concern for Huskisson that he would miss the departure of the Northumbrian with his wife onboard if it were indeed leaving.

Huskisson perhaps then crossed back to the ducal carriage and attempted to clamber aboard. The Chief Whip William Holmes MP called on Huskisson to do the same as him, namely to press his back against the carriage so as to fit into the 18 inch clear zone. Huskisson may have decided that his bulk would count against him. Holmes also had a singularly dubious reputation and had been no friend of the Huskissonites in Parliament (Moss had been concerned about his involvement in piloting the railway bill past the hostile Lords). For whatever reason, on the spur of the moment Huskisson may have felt viscerally disinclined to take his advice.

What happened next is unclear. In his statement to the inquest Wilton said that Huskisson was attempting to move around the carriage door, presumably to get to the entrance, but became entangled with it. His problem with his legs was compounded by a weakness in one arm which had previously been broken three times. By now the locomotive would have reversed gear and was braking to a halt albeit too late to help Huskisson. It collided with the carriage door, knocked part of it off and dislodged Huskisson whose leg fell across the track and under the wheels.

Huskisson would be dead by the day's end and Wellington's ministry would outlive him by a mere two months.

See also:

Hulton's view

Manchester & the way back